- IPR Intelligence

- Back to Main Page

Race to the Top 2 – EU Revs up with the Green Deal Industrial Plan and the 8 Questions for Investors

Introduction

EU efforts to compete against both China and the US in the clean energy sector have enormous consequences for investors. This paper will examine eight investment questions we consider most pressing arising from Europe’s revamped clean energy industrial policy, coined the Green Deal Industrial Plan (GDIP). The GDIP aims to prevent EU clean tech industry from decamping to the US (or any other location) and to protect the EU’s position as an attractive investment destination.

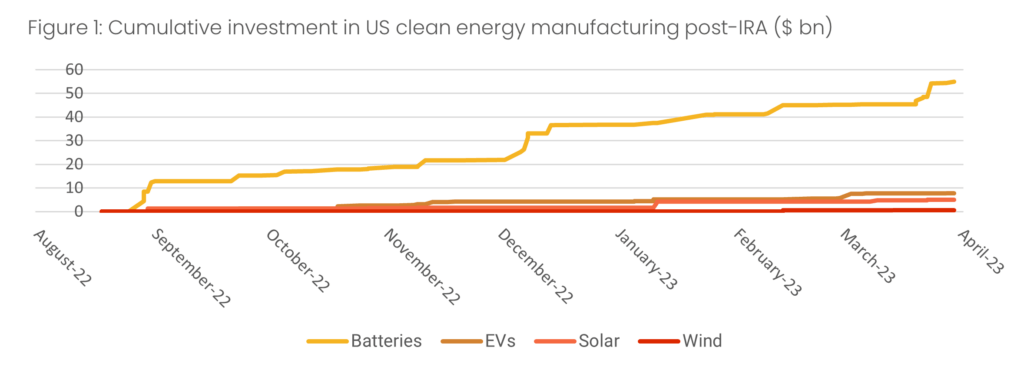

The competitive threat posed by the IRA is existential (Figure 1). Since the IRA was signed into law in August 2022, 91 projects worth almost $75bn and responsible for nearly 60,000 new jobs have been announced in the US, according to Clean Economy Works . US battery manufacturing facilities are by far receiving the highest influx of investment ($55bn). This has come at the expense of Europe’s battery industry, which saw its share of global battery investment plummeting from 41% in 2021 to 2% in 2022 just four months after the IRA was announced (BNEF). Additionally, up to two thirds of Europe’s 50 planned lithium-ion factories, representing 1.8 TWh of capacity, are now at risk of cancellation without further policy action in response to global competition.

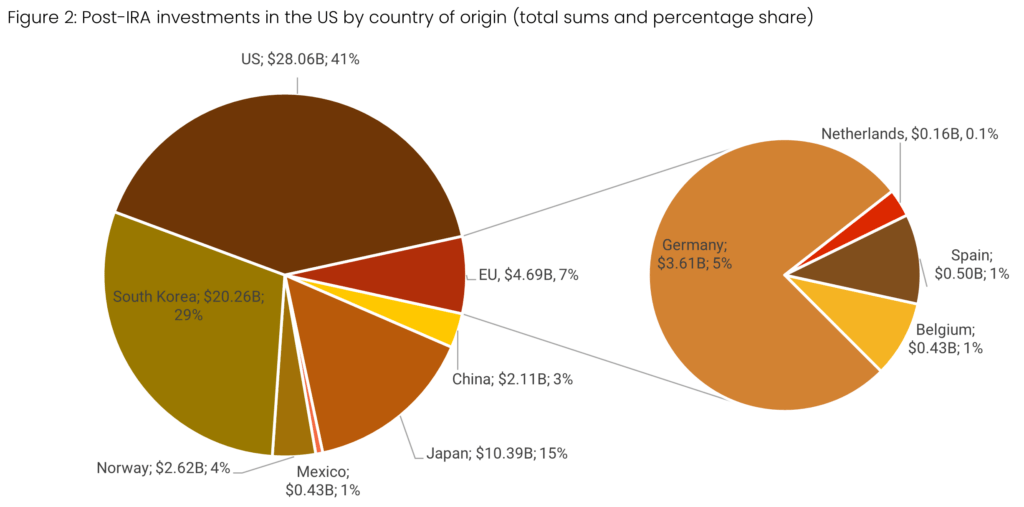

There is still time for the EU to respond to the IRA. A large-scale migration of EU clean tech companies to the US has not happened, with just 7% of US investment originating from EU countries (Figure 2). But the GDIP must address concerns from the likes of Northvolt, VW, and Freyr, who are publicly considering moving production to the US. Investors in the EU should also watch the capital from outside the continent. The world’s most advanced battery producers hail from China, Japan, and South Korea, and it is this cohort that the IRA has successfully enticed to the US, and who are set to benefit from large taxpayer outlays.

This is not just about batteries. Solar, wind, heat pumps, electric vehicles (EVs), carbon capture and storage (CCS) and hydrogen are all set to experience explosive investment as a result of dedicated government support. Entire industries to support these sectors will also offer jobs. The EU’s ability to build a clean energy economy has enormous geopolitical and climate repercussions as well. Given this, the GDIP is a undoubtably a step in the right direction for Europe. Here are eight burning questions we suggest investors ponder now.

1. What is the Green Deal Industrial Plan (GDIP) and why does it matter?

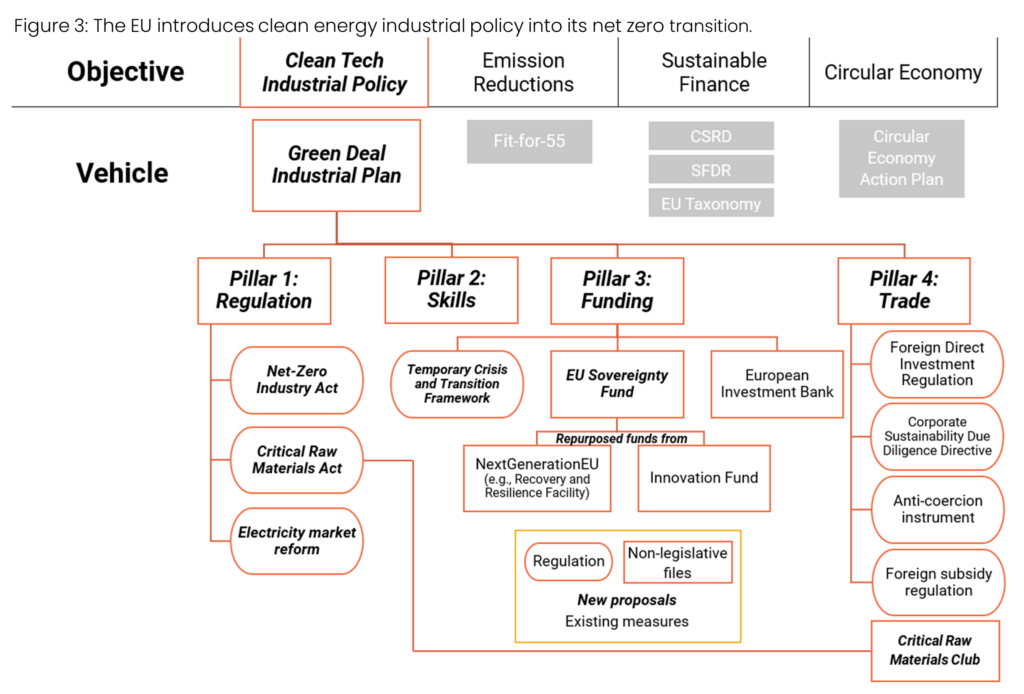

Until the beginning of 2023, the EU’s net-zero transition plan could be viewed as having 3 broad objectives: reducing emissions, making finance more sustainable, and creating a circular economy (Figure 3). The legislative weapons deployed to these goals ranged from the Fit-for-55 package (itself with fifteen areas under negotiation) to the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), and beyond.

In late 2022, the EU realised its climate transition plan was flawed. Existing regulations did little to account for the fact that, when faced with structurally higher energy prices in Europe and substantial tax breaks elsewhere, clean energy industry could stop investing in Europe altogether . Not only would this have an economic impact in Europe, but energy security would be unobtainable.The EU has designed an instrument, called the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, to prevent companies leaving Europe to benefit from more lenient carbon emissions requirements in other countries. Kaya has written extensively on the CBAM here. The CBAM might prevent carbon leakage but does not solve the market competitive issue.

To address this, the EU created an industrial policy specifically for clean technology called the GDIP. It consists of 4 pillars: streamlining regulations, developing worker skills, financing, and incorporating trade measures. Figure 3 shows where the GDIP fits in to the existing transition policy map. We highlight new elements in italics given some facilities are repurposed.

The GDIP matters for many reasons. Firstly, it makes the EU a more attractive destination from a regulatory perspective. It addresses problems such as the need for dedicated subsidies to clean energy sectors and prohibitively long permitting timetables for renewable energy and raw material projects. The Net Zero Industry Act (NZIA) and Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) in Pillar 1 are the most significant elements of the GDIP.

Secondly, it solidifies a shift in the global trade order. China and the US have already moved on this. Direct support for the clean energy sector combined with protectionism means investors have entered a post neo-liberal definition of trade. WTO and ‘free markets’ are diminished. Investment, security, and climate can no longer be viewed independently. Investment decisions need to consider political support for industry, potential trade barrier retaliation, and supply chain realignment. The risk of trade weaponization using various measures such as the Foreign Subsidy Regulation (Question 8) has direct implications for company revenues.

Lastly, the economics of investing in clean energy are fundamentally altered. The use of repurposed EU funds and enlarged state aid allowance means taxpayer money will flow directly to private enterprise. We will see more concrete examples of this in the EU as final language is negotiated. For example, in the US, Hanwha Q-cell’s $2.5bn investment in a new solar facility in Georgia will earn $561mn in tax breaks per year, meaning the US taxpayer is guaranteeing a minimum payback period of 4.5 years. While this structure is not directly comparable to the EU, the relaxing of state aid under the GDIP will allow ‘subsidy matching’ with the IRA.

2. Which sectors reveal the greatest policy ambition?

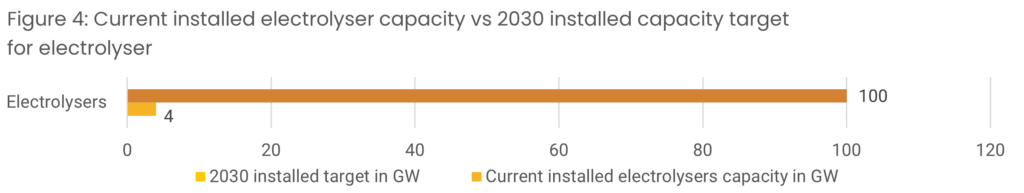

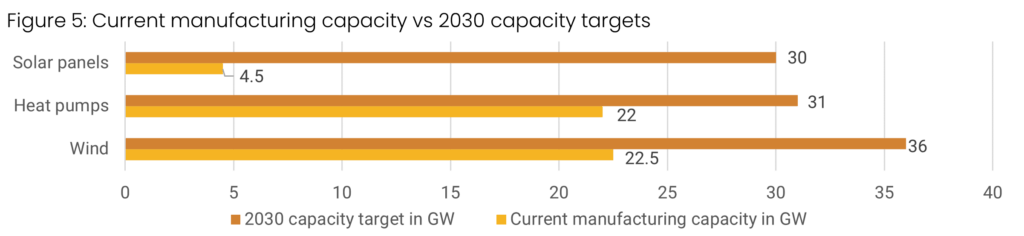

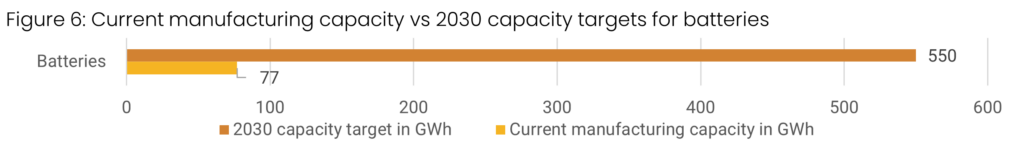

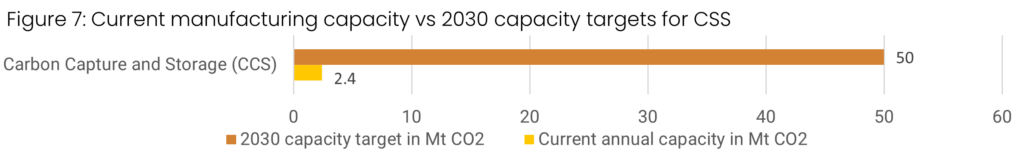

The EU Commission is telling investors which clean technology sectors are likely to receive the most government support. Aside from setting an overall target of producing 40% of the EU’s net zero technology demand domestically by 2030, the NZIA specifies eight strategic technology categories (Solar photovoltaic and solar thermal, onshore wind and offshore renewables, battery/storage, heat pumps and geothermal energy, electrolysers, and fuel cells, sustainable biogas/biomethane, carbon capture and storage, grid), setting targets for six of them (Figure 4-6). Biogas and grid do not have specific targets. Exact definitions of manufacturing capacity are expected to be finalised in the next year following EU Council and Parliament negotiations.

Wind and heat pump targets are notably lacklustre. Solar targets are more ambitious, signifying potentially more support for investors, but here we would caution that Chinese dominance of polysilicon and wafer production will be very hard to overcome and the 65% concentration risk limit in the CRMA could prove problematic (question 5). Battery production ambition is high, and we expect much more support to emerge, including subsidy matching, to compete with the IRA.

Electrolyser capacity is an area of potentially larger support. The EU is aiming for 100GW of installed electrolyser capacity by 2030, equalling 40% of projected global capacity. Nine European electrolyser manufacturing companies have a combined 4 GW of manufacturing capacity and anticipate 7.5 GW of capacity in 2023. Despite this, only 170 MW of electrolyser capacity has been installed to date indicating a lag between production and installation.

Seen as a whole, electrolyser technologies should not be held back by critical raw material (CRM) dependency as there are multiple technologies which use different minerals. But investors need be wary of putting all eggs in one electrolyser or company basket. For example, solid oxide electrolysers need significant amounts of the rare earth yttrium and/or scandium whose production is dominated by China while PEM and alkaline electrolysers need none. Investors should do their homework on supply chains carefully.

3. Will the GDIP be successful in catalysing clean tech investment in the EU?

The GDIP is a big step forward. We expect these measures to offer a compelling counternarrative to those eyeing a move to the US or China for clean technology investments, but elements remain unresolved.

There is no new money but plenty of repurposed money from existing funds (e.g., the COVID Recovery and Resilience Facility ). Given the IRA is theoretically unlimited in its ability to apportion taxpayer money to private companies, and the fact that the EU will face further costs related to the reconstruction of Ukraine, we see a scenario where additional money will be required. If this does not happen, then there is a risk that the clean energy industry may still disseminate outside of the EU.

The pillars of GDIP are heavy on goals but light on enforceable plans. There are lots of targets being set but few enforcement mechanisms. EU regulations are implemented at the member state level, and in most cases, funding is primarily mobilised by member states. Member states have different priorities and funding capability making it essential to evaluate individual investments both at the EU and member state level.

Nothing has been decided yet. Currently, the legislative acts within the GDIP are a Commission proposal. Investors will not have final clarity on elements crucial to investment until the EU Council and Parliament complete negotiations, likely sometime in 2024. This is a long-time horizon for investors needing clarity to invest in the EU, especially when clarity is already on offer from the US.

4. Is permitting reform the EU’s new secret weapon?

One of the biggest barriers to reaching the EU’s 2030 renewables targets is the slow permit-granting process. The Energy Transitions Commission (ETC) has estimated that up to 3,500 TWh of potential wind and solar energy could be unrealised by 2030 if permitting is not addressed. Prior to the GDIP, renewable energy project permitting times ranged from 2 to 7 years. Getting approval for a new mining project in Europe can take up to 15 years.

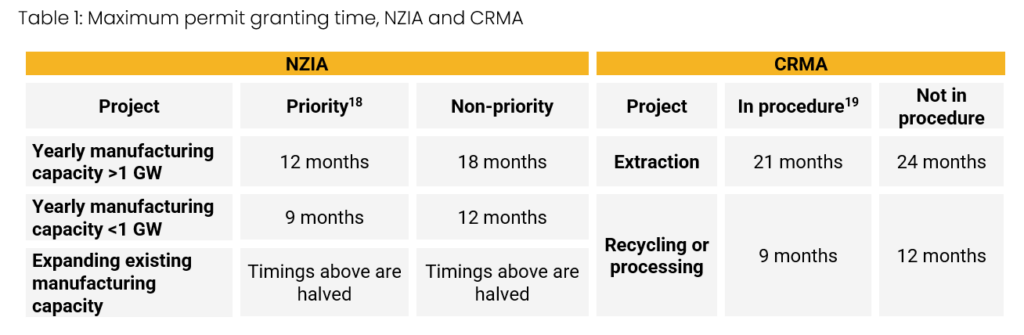

Permitting timelines for clean tech and CRM projects are dramatically shortened under the GDIP (Table 1). This should address a common complaint by investors: that things move too slowly in the EU. Within the GDIP, the NZIA dramatically improves project approval time limits and procedures. Designated ‘priority projects’ are eligible for additional permitting support. Crucially, under both the NZIA and CRMA, should there be no response from the relevant administrative bodies for priority projects within these times, the project is automatically considered approved .

Automatic approval is unlikely to look like an “EU override” of member state governance. Exceeding the maximum time limit will, however, allow for the developer to open a legal case against the member state. The principle of automatic approval is an important one, in that it places serious pressure on the member state to avoid EU court proceedings. For NZIA projects, this will only occur if project is not subject to an environmental impact assessment, or if the principle of administrative tacit approval does not already exist within the member state’s legal system. For the CRMA, this automatic approval is not granted in the case of extraction projects or if an environmental impact assessment is required.

These developments mean clean energy and critical material investors in the EU may find themselves advantaged relative to the US, at least for now. There has been no equivalent permitting breakthrough in the US, where permitting changes require legislative action. We do think there is the potential for US permitting changes to happen in 2023 given interest on both sides of the political spectrum, but it is a big question mark and a notable obstacle to US domestic clean energy buildout.

It will be up to each member state to implement the permitting standards. Permitting reform will play out differently in different member states, depending on strategic and industrial priorities. Another critical consideration is whether member state governments will have the resources to support such an endeavour, given the increased bureaucracy and labour inevitably required to meet reduced processing time targets. Evidence shows that reducing permit granting time results in the increased rollout of renewable projects at the member state level. Germany saw record onshore wind capacity growth in 2022, which BWE say was largely due to ramping up projects as fast as possible and accelerating permits.

And member states can take action to move even faster. In France, proposed updates to the industrial green policy aim to reduce a 17-month permitting period by bypassing the National Commission of Public Debate’s approval, so long as the project directly contributes to French decarbonisation targets. The Netherlands has reduced permitting times significantly over the last decade, and Dutch infrastructure tenders have consequently become highly competitive among developers.

5. Can the new Critical Raw Materials Act address the EU’s enormous mineral needs?

The EU will need to extract, recycle, and process far more CRMs to meet its climate transition goals. EU demand for rare earth metals is expected to increase 4.5x by 2030. Lithium demand is set to increase 11x by 2030, and 57x by 2050. EU green industry is highly dependent on imports of raw and processed CRMs.

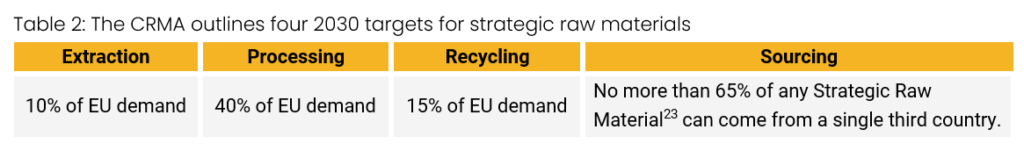

The GDIP addresses this by setting 4 targets in the CRMA . By 2030, at least 10% of EU demand for ‘Strategic Raw Materials’ (SRM) must be met by domestic extraction, 15% through recycled waste and 40% through domestic processing. To diversify supply chains, no more than 65% of any SRM can be sourced from a single third country. The EU currently extracts negligible volumes of SRMs and only houses significant processing capacity in cobalt (15% of global output). China supplies 98% of the EU’s demand for rare earths.

The EU needs to address the uncertain and volatile economics of CRM extraction, processing, and recycling. The Commission may consider market interventions such as price floors and Contracts-for-Differences (CfD) or imposing sustainability criteria on traded raw materials. Without these measures to level the playing field, EU industry will not be able to compete with subsidy-backed overseas competition.

The EU will need to be more cautious than the US when it comes to implementing trade protection for domestic mining industry. The US can, and likely will, use a combination of these measures, leaning more toward sustainability standards, but the EU would be exposing itself to a trade war it could not win against China if it tried to develop a domestic industry with trade protection.

The EU may also seek to enhance CRM investment profitability through a transatlantic partnership. The US is actively exploring such arrangements, including the creation of the Mineral Security Partnership, and forming bilateral agreements on critical minerals with Japan and possibly the EU. Similarly, the EU is forming bilateral partnerships that embed ESG (environmental, social, and governance) criteria with countries like Namibia and Kazakhstan and looking to form a Critical Minerals Club with the US and other mining countries, although it is moving slower and with less determination.

What happens when a raw material is designated as ‘strategic’? This designation is potentially powerful as it would mean that extracting, processing, or recycling of an SRM benefits from a faster permitting process, as per Table 1. The proposed time limits for permitting are a significant boost to bankability as cash flows are brought forward.

Knowing whether a metal is strategic is a pertinent question for investors. Steel and aluminium producers, whose businesses have taken a hit from high energy prices and Chinese competitio, are clamouring to be included on the list .

6. How does Europe’s new industrial policy incorporate ESG?

In a post neo-liberal trade world, the EU is setting up to solve for three objectives simultaneously: protecting domestic industry, reducing geopolitical supply chain risks arising from dependencies on third countries, and achieving ambitious climate goals. Incorporating ESG standards into public procurement of net-zero technologies provides a mechanism by which the EU can meet all three objectives. Public procurement procedures refer to the methods and rules for awarding contracts between public authorities and private companies for the provision of goods, works, or services. These procedures, and how much money or access is offered by the government, plays a significant role in industrial policy.

The GDIP does not call it ESG, but it’s there. ESG has expanded from a term that referred to the protection of human rights and the environment to one that includes industrial resilience, energy security, and strategic autonomy. This is what the EU had in mind when designing its new industrial policy, particularly in public procurement procedures of net-zero technologies, where ESG is instead referred to as sustainability and resilience .

Prior to the NZIA, winning tenders was purely about cost. Now sustainability and resilience must account for 15-30% of the weight of the award criteria for net-zero technology procurement. One caveat to this is if meeting the 15-30% threshold requires bidders to buy equipment at a cost difference of >10% compared to conventional equipment, the sustainability and resilience considerations no longer apply (excluding abnormally low-priced tenders covered by rules on distortive practices under the adopted foreign subsidies regulation). This is to prevent the wealthiest bidders from obtaining rights to a project, something that state-backed Chinese companies are well-positioned to do.Note that these provisions will not apply to smaller public bidders and tenders below EUR 25mn for two years after the NZIA enters into force.

Sustainability and resilience will be defined at the member state, not EU, level. It will be based upon a set of cumulative criteria, including environmental sustainability beyond the minimum legal requirements, contribution to energy system integration, and the proportion of products originating from a single source of supply .

How member states define sustainability and resilience under the criteria will depend on national priorities. The emphasis on each of the three strategic imperatives outlined above will vary, with countries like the Netherlands prioritising the reinforcement of domestic industry, whereas countries like Denmark or Sweden may lean more heavily on achieving ambitious climate goals. However, it is unlikely that member state interpretations will vary significantly, as overall the strategic imperatives apply across the bloc.

7. Can the GDIP save the car industry in Europe?

The EU automotive industry is facing a wave of fresh challenges. Europe produces ~20% of all vehicles worldwide, and the auto industry is responsible for 7% of EU GDP, but the threats to this industry are growing. These threats include:

- a recently agreed phase out of internal combustion engines in Europe by 2035 thus accelerating a need to produce EVs,

- non-assured access to CRMs required in EV battery production , notably lithium ,

- potential loss of sales in the domestic US market given local content requirements in the IRA, and

- battery production facilities moving to the US for higher tax incentives

The above factors indicate that EU EV car manufacturing is not vertically integrated. Automotive companies like Tesla or BYD that have deep vertical integration and closed supply chains are benefitting from significantly lower costs that will soon allow them to halve the cost of electric cars in a ‘race to the bottom’ . The CRMA and NZIA have been designed in part to address this through boosting secure access to CRMs, targeted support for EU automakers across the entire supply chain and facilitating alliances among automotive sector stakeholders across the bloc.

8. How will China dependency be addressed?

The GDIP involves a targeted refocusing on the use of existing subsidy and anti-coercion instruments to promote strategic autonomy, rather than an introduction of new trade measures. Investors should closely follow the usage of these instruments as the EU attempts to balance developing its own industry while avoiding antagonizing its main supplier of these products, China. A commonly cited example of the EU’s reliance on China is the >90% dependency on components for solar photovoltaic technologies, but there are many more examples which Kaya has covered here.

EU politics on China are an unresolved issue. The EU relationship with China is shaped by the interplay of two forces; an imperative to preserve good relationships with the US and the need to avoid supply chain disruptions in key industries. Political factions within the EU have different views.

The Commission is aligning strongly with the US, saying as much in a recent visit with President Biden. While trade lies in the purview of the Commission, notable countries in the Council including Germany are arguing that national security issues need to be considered and that any hard line against China is too great a risk.

With the GDIP, the EU is developing a new toolbox of trade instruments to address the China relationship. The Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR) requires companies operating in the EU to notify the Commission about foreign financial contributions received, which allows the EU to monitor whether companies are receiving distortive support from third-party countries.

If it is found that foreign contributions are distorting the single market, measures would be imposed to redress these effects, including fines or repaying received support. If the firm fails to address the distortion, the Commission could reverse any M&A activity in which the company has engaged, prevent planned M&A, and/or prevent the firm from participating in public tenders.

The Commission is also introducing an anti-coercion instrument that enables the EU to impose import tariffs, trade restrictions, or public procurement measures against any third country that targets the EU with economic coercion measures. These new measures would complement existing ones such as the EU framework for screening foreign direct investments, the EU Foreign Investment Regulation, which is currently being revised by the Commission.

More counter-China measures will be introduced later in the year. In a recent speech, EU Commission President von der Leyen revealed that the Commission is thinking of adopting a new “Economic Security Strategy” that will include restrictions on outbound sensitive technologies that could lead to national security risks. Most likely the instrument would be targeted to technologies such as microelectronics, quantum computing, robotics, artificial intelligence, and biotech . To date, these actions have been bilaterally addressed such as the Dutch governments banning of semiconductor technology to China .

The use of these measures by the EU increases the risk of retaliatory action by China up to and including targeted trade wars. China has already threatened a reciprocal ban on certain components for solar PV production such as large wafers, black silicon, and ultra-efficient silicon ingots .

We assess the EU has more to lose in these targeted trade wars when it comes to clean technology and CRMs. This creates a challenging environment for business and risks further supply chain disruptions. There is also a risk that firms that undertake business on both sides of the Atlantic, and who are planning to harness the benefits of both NZIA and the IRA, will find it increasingly difficult to see those benefits materialise .

Author: Brian Hensley – brian.hensley@kaya.eco