- IPR Intelligence

- Back to Main Page

A New Collective Quantified Goal

COP efforts to catalyze $1 trillion in climate finance to achieve the goals of the Paris Agreement

Later this year COP 29 Parties will negotiate and adopt a major component of the Paris Ratchet process, a new collective quantified goal (NCQG) on climate finance, which aims to significantly ramp up international financial support for climate action.

Building on a pledge by 43 developed nations made at COP15 in Copenhagen (but never officially negotiated) to mobilize US $100 billion per year by 2020 (later extended to 2025) the proposed NCQG has the goal to lift to $1 trillion per year. Adoption of the NCQG is considered a critical component of the Ratchet process, demonstrating seriousness of intent in mobilizing climate finance to match and drive ever higher ambition from emerging and developing economies (EMDEs) in the next round of NDCs. This new round of NDCs is the foundation component of the Ratchet process, to be confirmed at COP 30 in 2025.

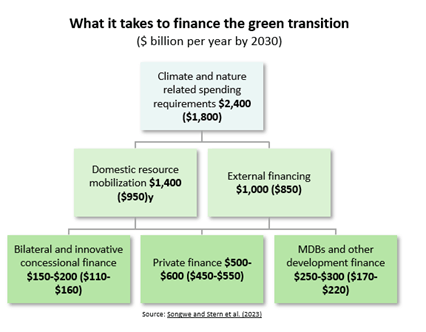

If adopted, the NCQG will be the first negotiated financial commitment under the Paris Agreement process. And if met, it could represent a significant portion of the total developing country needs for mitigation, adaptation, nature-based solutions and loss and damage. A 2023 Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance (IHLEGC) report, estimates total needs at around $2.4 trillion (excluding China) and a new determination of needs report will be published this northern summer.

However, parties and observers acknowledge that commitments to date have fallen short of the $100 billion commitment. An OECD report last year found that in 2021, total climate finance mobilized reached $89.6 billion, with public sector finance accounting for over 80% of this. Negotiating parties can only commit public funding, with analysts suggesting this could reach a maximum of $500 billion per year. Scaling from billions to trillions will therefore require significantly unlocking of and increasing private capital flows.

The risk factors in scaling private sector investment into the developing world are well documented and so using public sector money to de risk those opportunities remains crucial.

Figure 1

NCQG – A brief history, challenges and key priorities

In 2009 at COP 15, Parties committed to mobilizing US $100 billion per year by 2020 to address developing country climate action needs. Six years later in Paris, COP 21 Parties agreed that the NCQG would be set before 2025 with a minimum baseline of $100 billion per year and a mandate to take into account needs and priorities of developing Parties in accordance with Article 9.3 and by making financial flows consistent with a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development.

At COP 28, work began to develop a framework for drafting negotiating text. In April of this year in Cartagena, 300 Parties and non-Party stakeholders convened at a first in a series of meetings that will conclude in October in the run up to Baku COP 29 negotiations at the end of November.

Key priorities raised by EMDE parties include addressing “un-enabling environments” which have impeded access to capital pre-2025. This has included high cost of capital, high debt burdens, and imbalanced geographical concentration of finance. Parties emphasized the importance of grant-based and concessional finance.

EMDE parties have also proposed finance be structured across mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage on a needs-basis and some called for explicit burden sharing across developed country contributors to increase accountability and predictability of finance flows. Figure 1 provides an annual estimated breakdown of investment/spending requirements for climate and sustainable development by 2030.

Another hurdle is that some developing countries have advanced since the inception of the Paris Ratchet process. As a result, determining which countries fall into each categorization (donor versus recipient) becomes more complicated. Developed countries for example have called for China, for example, to join the donor pool and indeed a recent ODI report ranks China as the 11th largest contributor to climate finance ahead of many Annex I countries. To achieve up to a 10x increase in finance, experts have recommended mobilizing domestic resources including through tax revenues, carbon taxation and elimination of fossil fuel subsides; multilateral development banks sharing risk to catalyze private finance, a tripling of concessional finance from developed countries with support from carbon revenues from underlying projects.

The Bonn Conference (SB60)

This month at the June 2024 UN Climate conference in Bonn, finance negotiations faced headwinds as developed countries such as the US and EU were reluctant to propose specific targets, and disagreements continued over which emerging economies should fall under the donor base.

G7 countries have also called for wealthier emerging economies such as China and Gulf States to join the donor pool while these countries maintain that developed nations should continue to contribute in line with their historic emissions contribution.

Recent policy uptick – IPR tracking

Although finding consensus amongst Parties as they continue to advance on the NCQG work program looks challenging, IPR has tracked in recent months a spike in policy announcements from countries active in upcoming negotiations. EMDE countries seem to be positioning themselves by improving their regulatory environments and more explicitly tying their commitments to concessional funding flows from developed countries. These include:

- India announced $67 billion investment over the next 5-6 years in the energy sector, with earmarked for renewables. The Indian government also simplified its approval process for solar energy to bolster investments, in addition to allocating $9 billion to accelerate clean energy technology adoption.

- Mexico, a key negotiator in climate finance negotiations, announced 20 new protected areas encompassing 2.3 million hectares, covering about 1.2% of its land surface, despite a series of budget cuts to environmental agencies.

- Vietnam announced a Hydrogen Energy Strategy which aims to produce 100-150K tons of clean hydrogen annually by 2030, rising to 10-20 MT by 2050 and seeks foreign capital to invest in green and blue hydrogen production.

Please see IPR’s interactive tool to search for relevant EMDE country policies by sector.

Outlook

A failure to significantly ramp up climate financing at COP29 could undermine the Paris Ratchet process.

IPRs Q1 2024 Quarterly Briefing has tracked funding gaps in Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) commitments to phase out coal and advance renewable energy deployment in key EMDEs. These include a $81.2 billion gap in South Africa, a $46.9 billion funding gap in Indonesia and a $119.2 billion gap in Vietnam.

Funding gaps coupled with announced coal and renewable plans fall short of JETP expectations, leading IPR to downgrade its climate policy forecasts for both Indonesia and South Africa.

A massive scaling up in funding will also be critical for financing nature-based solutions, examined in IPR’s March 2024 Land and Nature Briefing. NBS is suffering from underinvestment but will play a crucial role in ensuring temperature stabilization through carbon sequestration.

Conclusion

While the NGQC is a public finance initiative, resolving some of the outstanding differences on display at Bonn, leading to success at COP29 will add vital momentum in the run up to the 2025 Ratchet. Key multilateral events to come include the 12-14 July G20 summit in Brazil the 21st October to 1st November Biodiversity COP16 in Cali, Columbia and COP29 itself, from 11th to 22th November in Baku, Azerbaijan.

Effective implementation of underlying policy measures and subsequent investment will have a positive impact on private finance, assisting the ‘catalyzation’ ‘crowding in’ and ‘blended finance’ goals policy makers have repeatedly called for since COP15 way back when in Copenhagen.

IPR will continue to monitor progress on the NGQC and other major climate policy trends in 2024 via our Quarterly Briefing webinar series with Principles for Responsible Investment. in February 2025 we will release our annual review, assessing developments including outcomes and impacts of COP29 in Baku.

Next IPR Webinar Event

IPR / PRI Quarterly Briefing: Global climate policy developments – Quarter 2

Wed 10th July 2024 – 14:00 BST Register here.