- IPR Intelligence

- Back to Main Page

Direct Air Capture – Policy Support is Essential.

Direct Air Capture (DAC) of CO2 and its storage – DACCS – has been a feature of the Inevitable Policy Response (IPR) analysis and forecasts since 2020. Policy emerges as central to any scale up as clean energy technologies are developed.

From a policy design perspective, it is relevant that DACCS can be deployed in two ways:

- To remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it in a permanent way, in other words to deploy it as a carbon removal. This could assist in hard to abate sectors such as industry and land. For instance, the IEA NZE 1.5C low overshoot scenario assumes 0.6GT of DACCS by 2050. Further, any more significant temperature overshoot above a 1.5C level, such as in the Inevitable Policy Response Forecast Policy Scenario (IPR FPS), could be addressed.

- To produce CO2 feedstock for synfuels, which looks more of a stretch compared with other opportunities, or to be used in building materials such as cement. In effect this is using the CO2.

For a technical description please see the Oxford Institute of Energy Studies’ Energy Forum summary paper on ‘The Challenge of Scaling Direct Air Capture and Storage’ and a new study from IPR on DACCS, ‘Quantifying the Investment Opportunity.’

Decarbonisation the Priority – NETS for Overshoot

The risk with deploying DACCS to address existing emissions is that like any Negative Emissions Technology or NETs, apart from helping to address hard to abate emissions, it can be used to offset any type of existing emissions, and therefore distract from addressing the underlying need to decarbonise.

This points to the need for policy and technology to address decarbonisation in the economy as its primary focus, at least for the time being. This is best done via demand side management such as emissions targets for vehicles, incentives for green technologies in early stages and in certain cases, outright bans or performance standards.

This influences demand for carbon intense industries and products. Stronger demand side management leaves more flexibility for NETS such as DACCS to focus on the hard to abate sectors. The importance of NBS and afforestation cannot be underestimated as the first step to scale in NETS deployment. The IPR FPS assumes 4GT of NBS by 2050, dwarfing its forecast 0.6GT of DACCS.

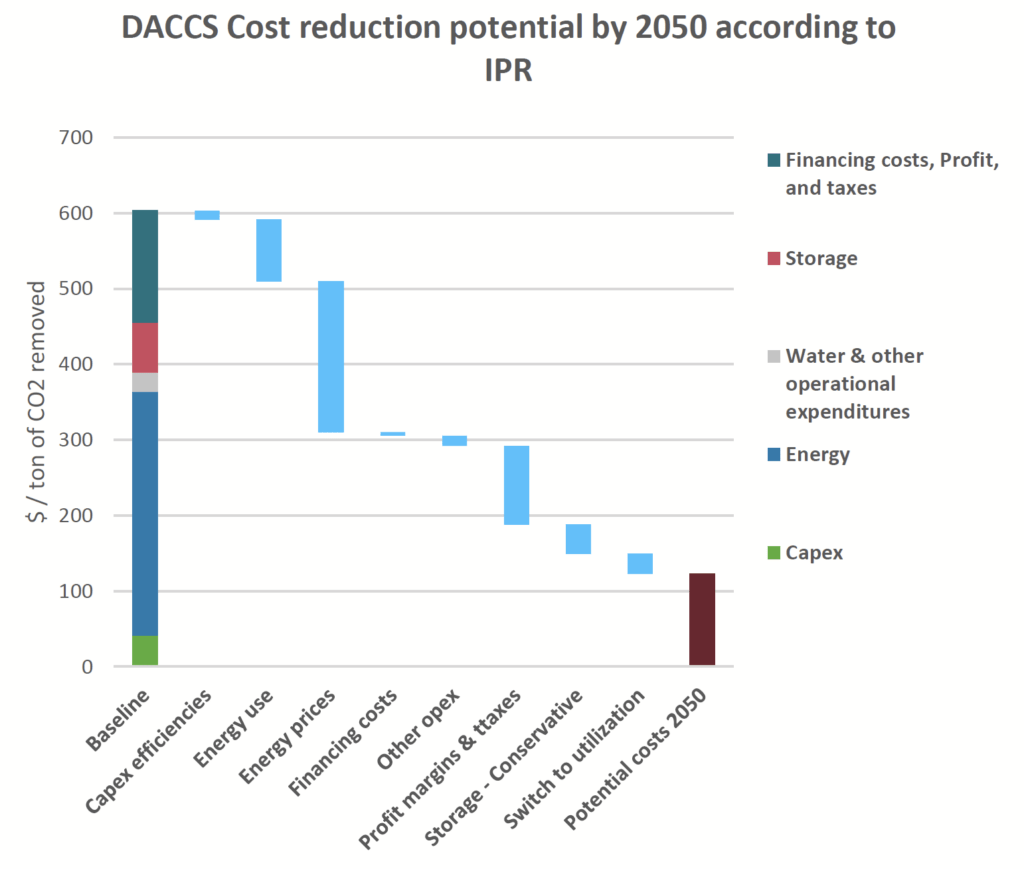

The challenge with DACCS is that currently the cost in its various applications seems set in a broad range with a pre-subsidy range around $600tCO2 possible in 2025 (See IPR paper). Significant policy incentives will be crucial to enable innovation, and scale up, to bring costs down. The Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM) has created early demand to finance DACCS, but this seems unlikely to trigger deployment of DAC and storage at sufficient scale.

Applying Existing Policy Tools

Governments need to provide clear (finance relevant) policy direction, up to and including legislation, to provide business certainty.

Policy tools are fairly straight forward and can be taken from the current climate playbook:

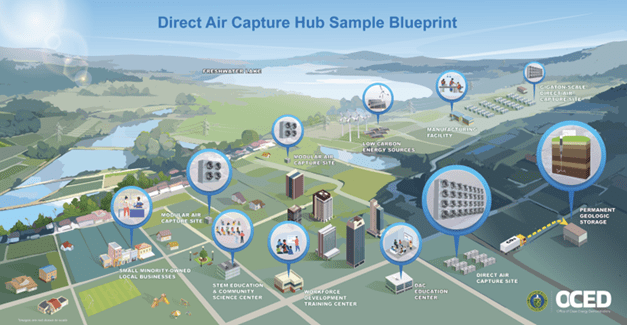

- Direct funding for R&D such as the EU Innovation fund. For constructing large-scale first-of-its-kind (FOAK) plants in DAC Hubs as in US IRA . Taking a stake in a project could also be possible or via first loss loans. (See Figure 1)

- Direct incentives through tax credits or for production such as under the updated US provision 45Q in the US IRA 180 $/tCO2 captured and stored and $130t used. Importantly this can be claimed at only 1000t a year size which encourages early startups.

- Carbon pricing. As such there is no carbon pricing regime that includes DACCS. But regions such as the EU and China have carbon markets. These could be adapted to include DACCS. In a global context UN Article 6 covering carbon markets is an important instrument.

- Contracts for difference such as in the UK are also vehicles of support.

- Public procurement of DACCS credits and through reverse auctions could be used for price discovery and to launch major programs. These could be a key in a major programme to address overshoot.

- Development banks could become involved where applicable in order to reduce financing costs, a small but important feature of the cost landscape (Quantifying the Investment Opportunity).

Figure 1: DAC HUB Blueprint

This mix of policy measures can be summarised by three broad approaches for governments to achieve scale:

- Bring DACCS costs down via direct subsidies such as tax credits.

- Directly procure the DACCS credits.

- Make the cost of DACCS attractive verses emitting, through carbon markets.

Driving DACCS Costs Down

There is also a role for agreed Life Cycle Analysis of the various types of DACCS, and accounting frameworks to assure carbon offsets that are sold either bilaterally or through the Voluntary Carbon Markets (VCM).

In the future, standards aligning with UN Article 6 will be required.

Right now, the demand for DACCS comes from the Voluntary Carbon Markets and the need for high quality credits. The uncertainty around forests is having a major impact on VCMs right now. The need for assurance of measurable performance of C02 capture looks likely to be a significant driver.

JP Morgan Chase paid 800 $/tCO2 in May this year after tax incentives are taken into account in the VCM market, but demand is likely to be constrained at these prices. Reaching 1GT captured by 2050 would be unlikely at these prices.

While costs are expected ultimately to drop to $100-150, this requires, as per clean energy transition, a supported scale-up in the earlier stages. Accordingly, it seems incentives will have to rise substantially to start the level of scale up that could lead to a virtuous circle towards cost reductions.

The $180/t of IRA tax benefit for DACCS in the US is meaningful, but not sufficient to stimulate the multiple megaton projects that will be required to push R&D, provide learning by doing opportunities and deliver economies of scale.

Furthermore, this needs to happen worldwide, not just in the US. Precise learning curves to get cost reductions are not easy to estimate in new technologies. Scale is key.

IPR FPS assumptions are as follows:

Figure 2: IPR FPS 2023 DACCS cost reduction.

Governments may see decarbonisation of hard to abate sectors as reason enough to make significant investment in the next decade.

Tackling Overshoot

However, it is in the context of addressing overshoot of any 1.5C temperature outcome that policy design could expand to be far more comprehensive, because if that scenario prevails, then carbon removals including DACCS will be required. NBS will be hard to push much beyond the 4GT by 2050 given the land constraints.

Overshoot with multiple significant climate events would usher in a new world, which would need to be addressed at a global level. Deciding when overshoot of the key 1.5C level is happening will be contentious but, by the early 2030s the IPR FPS sees this as confirmed, and average annual temperature itself will be overshooting 1.5C in particular years, ahead of that.

Any associated severe climate events or mass migration will bring into question who is ‘responsible’ for the overshoot and that will reach back into the history of emissions since the late eighteenth century. These will not be easy discussions.

It is most likely discussions to resolve overshoot will start in the context of the IPCC as the apex climate body (which could begin to address the issue in the context of carbon markets in Article 6).

It seems likely that as overshoot happens and climate impacts gather pace, then social tipping points will also be reached, leading to collective recognition that action will be required to stabilise the climate. In other words, the need to address overshoot may simply become ‘inevitable.’

As in the case of the Green Climate Fund, who pays for the action to address the temperature. CO2 overshoot will hold the key.

A Role for G20?

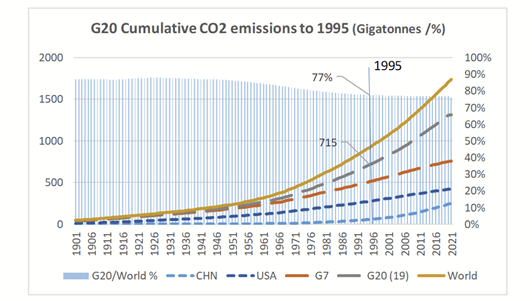

With respect to coordinating and setting the direction for collective global initiatives, the G20, which is responsible for 75% of historic emissions, has proven to be an effective apex international organisation. It brings together the wealthier nations, it bridges the global North and South, and it includes both hydrocarbon producing and net-hydrocarbon consuming nations.

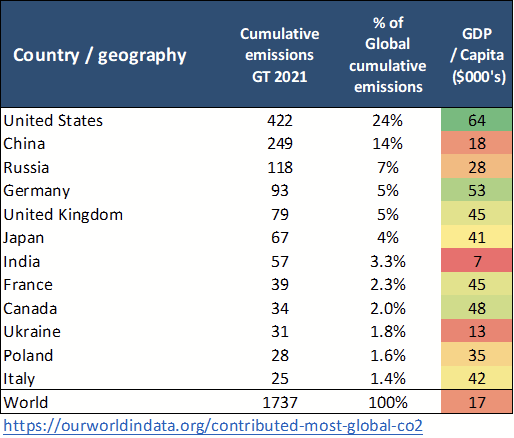

Furthermore, it has successfully addressed global issues in the past. However, it is important to note that still developing countries in the G20 make the case that the OECD members have reached a higher level of wealth, that they too have a right to achieve. Hence GDP per capita is also going to have to be considered.

Figure 3: G20 Emissions

Figure 4: Cumulative emissions by nation

An agreement sponsored and paid for by the G20 may pave the way for historic emissions to be removed. And at the same time (in effect), create a greater share in the remaining carbon budget for the smaller emerging and developing countries.

How these countries finance these costs will be a huge debate.

- Unrestricted government borrowing such as in Covid would only eventuate in a true crisis that will then take some time to solve, given lags. That is always possible from the 2040s, possibly even before.

- Using carbon market revenues is a pathway.

- Carbon taxes skewed towards high emitters would be seen by many as an equitable approach. Indeed, it’s possible some high emitters such as Oil & Gas corporates have the skills and technology to deploy DAC themselves so they would be, in effect, taxed on one side of the business and rewarded on another – potentially a very effective way of netting emissions.

- Again, with the caveat the underlying trend in oil and gas use needs to be downwards. A meaningful global carbon tax would keep prices higher as demand fell, again encouraging substitution.

Don’t Forget Plan B

It makes sense that policy further encourages the development of DACCS within the overall context of pushing as hard as possible for low overshoot 1.5 degrees, while in effect preparing a ‘Plan B’ to tackle overshoot if and when that may be required. The IPR FPS forecasts that fallback will be needed.

There is also a role for governments in the coordination and planning of DAC and storage hubs. And DAC accounting, definitions and standards to assess of life cycle impacts of DAC removals all need to be developed and agreed sooner rather than later.

Governments should also be bold in shouldering the costs now, to get the learning curve of reducing costs in motion, as they were once with renewable energy, particularly solar power.

Planning for the longer term should not wait long.

———————————————–

Mark Fulton is Founder of the Inevitable Policy Response (IPR).

This post forms one element of a three-part series from IPR on DAC, covering policy, engineering and investment challenges. The IPR investment paper can be found here.