- IPR Intelligence

- Back to Main Page

Clearing the Smoke from the Anti-ESG Wildfire

Authored by: Brian Hensley, Chris Schenker, Sara Romby and Lara Gutierrez Santander at Kaya Partners,

This substantive paper prepared by Kaya Partners for the Inevitable Policy Response (IPR) shows that the anti ESG movement is real and very noisy. It is not, at present, affecting the key capital flows in the US economy supporting the climate transition. However, engagement initiatives are likely to prove more complex to navigate. The insurance sector illustrates how withdrawing from a voluntary climate alliance does not alter the needed business decisions and strategy.

This analysis is a valuable addition to the debate, giving much needed clarity on an emotive topic. As an economic forecast based on research looking for materiality, the IPR Forecast Policy Scenario offers a high-conviction, real-world approach to investors on the ongoing climate transition

Mark Fulton, Founder, Inevitable Policy Response

Download the paper offline here

Key Findings

- ‘Anti-ESG’ in the US has morphed into a wildfire, with both legitimate flames and political smoke. Distinguishing the difference is difficult.

- Anti-ESG cannot be ignored. At a minimum, the well-coordinated anti-ESG movement adds transaction costs and complexity to financial and corporate strategy when it comes to climate-related activities. At its worst, it represents a conservative overreach into financial and corporate decision making inimical to good governance.

- Corporations, not just financial institutions, have cause for worry. Anti-ESG actors are increasingly targeting companies broadly. Targeting is done either directly via wording in laws against screening (so-called “anti-boycott” laws) or indirectly by targeting proxy voting activity.

- The evidence is mixed on whether anti-ESG or ESG is currently ‘winning’. The volume of anti-ESG bills dwarfs pro-ESG, accelerating sharply in 2023. When it comes to bill introduction, more states (32) are pure anti-ESG than pro-ESG (10) and voluntary climate alliances are under strain. But the failure rate of anti-ESG bills is high and many anti-ESG laws are ultimately watered down as Republican lawmakers themselves rebel against the adverse consequences embedded within. Executive orders at the state level and financial asset flows add to a nuanced story.

- Real economy capital flows, i.e., clean energy infrastructure investment, are not affected by anti-ESG while ‘engagement’ as a stakeholder process may be threatened.

- There is no monolithic architype for ESG legislation. A ‘drop down’ menu of bills, based broadly on either anti-screening laws (whose proponents refer to them as ‘anti-boycott’) or on ‘restriction of ESG factors’, is being bolted together in different states. We look at a case study of anti-ESG legislative packages in Florida and Texas, noticing a politics vs. substance distinction.

- Policy makers and regulators cannot be expected to come to the rescue when it comes to antitrust and fiduciary duty in the US where the legal and political landscapes are defined differently than those of the UK or EU. We offer a comparative framework between the US, UK, and EU to clear smoke from the flames.

- Anti-ESG efforts present opportunities and not just risks. One such opportunity is the pursuit for consensus on climate related financial risk in the US. The exit of 5 major insurance companies from premium writing in the US, citing climate risk, while simultaneously 13 other insurance companies exit from voluntary collective cooperation on climate reveal the perverse discrepancy between reality and politics. We look at insurance premium rises in primarily anti-ESG states and an unresolved tension between state regulators and federal agencies when it comes to incorporation of climate risks in insurance rate calculation. Ultimately the questions being asked in this debate will need to be resolved.

1. Introduction

In this paper for the Inevitable Policy Response (IPR), Kaya Partners analyses the state-of-play of the anti-ESG movement in the US. 1 In so doing, we attempt to offer a degree of clarity for investors navigating an increasingly muddled and acrimonious landscape. We focus on climate, which is but one part of E.

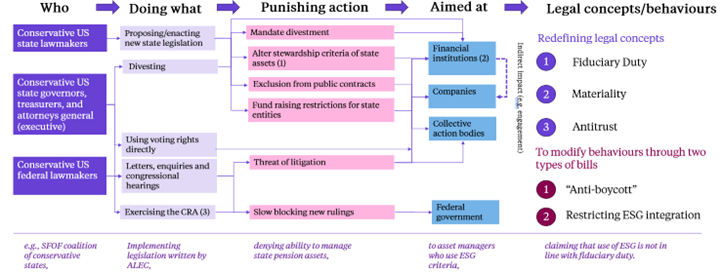

The anti-ESG movement is like a wildfire. Anti-ESG actions are characterised by a multitude of burning hotspots spewing pollutants across borders. Even if an individual blaze is contained, another pops up. A thick haze of smoke hinders investor ability to adopt safe pathways of action. Figure 1 outlines the structure of the anti-ESG movement. The individual sections are explained further below.

Figure 1 The anti-ESG movement in one slide

Source: Kaya Partners, 2023

Notes: (1) State pension funds and retirement systems, (2) Mainly asset managers, banks and insurers (3) Congressional Review Act

Who is winning the battle? The wildfire is doing damage. Republican law makers in the US have been relentless, having filed 112 2 anti-ESG bills across all states since the beginning of 2023. More US states (32) have enacted anti-ESG policies than have enacted pro-ESG (10) policies. Additionally, since 2021 more anti-ESG laws (44) have been passed than pro-ESG laws (20). We see evidence that flows into public ESG funds have slowed relative to the broader market, fewer sustainability funds are being launched and large institutions are distancing themselves from high-profile climate groups.

However, anti-ESG bills have a higher rate of failure. The reasons for failure reveal glaring inconsistencies and legal vagueness in the legislation which would harm both the states wishing to enact the laws and ‘trap’ financial companies between state and federal obligations.

While some corporate actors are stepping back from using the term ESG, the highest profile example being Larry Fink who referenced the ‘politicize(ation) and weaponize(ation)’ of the expression, 3 other actors are becoming more vocal in opposing anti-ESG tactics. Examples of the latter include the Kentucky Banking Association suing the Kentucky Attorney General for allegedly exceeding his authority by demanding documents from the nations six largest banks concerning their use of ESG. 4

A comparison of legislation between Texas and Florida reveals different objectives of anti-ESG. While both possess a political character, bill construction in Texas is designed explicitly to protect sectors of the economy, notably fossil fuels, while in Florida this is not the case.

While ESG was developed by and for investors, it is increasingly integrating into non-financial corporate strategy and, from there, the real economy. The anti-ESG movement is taking note, similarly including non-financials in anti-screening (so-called “anti-boycott”) legislation (see Box 1 below) and leaving the wording of other bills comprehensive enough to spread the wildfire beyond finance.

Smoke or fire? This depends on the issue and the jurisdiction. Antitrust, fiduciary duty, and materiality are central issues being targeted by the anti-ESG movement. Clarity is emerging in antitrust in the UK and the EU, when it comes to participation in voluntary alliances, but not in the US, where antitrust policy is set at both federal and state levels, is treated as a criminal act with more severe financial penalties, and is shaped by the enforcement priorities of the administration in power as well as judicial precedents. Fiduciary duty is more complicated, as it is more open to interpretation. In the US, states hold significant power in interpreting fiduciary duty as it relates to state pension systems. It is also worth noting that ESG pushback in Europe is of a very different flavour than the US, more driven by concerns about greenwashing than fundamental questioning of validity of ESG integration.

Climate risk is real and must be priced, regardless of politics. This is being shown by the most advanced practitioners of climate risk pricing, insurers, withdrawing from segments of the US market due in large part to increasing impacts from climate change. They are doing this even as they exit from voluntary climate initiatives due to a threat of litigation from anti-ESG factions.

A cascade of climate induced systemic financial risk is thus entirely possible as uninsured portions of the economy transition to the taxpayer. Perversely it is the anti-ESG states that are seeing the largest hikes in insurance premiums and who are also now actively seeking to stymy insurance companies from incorporating ESG factors in their premium calculation. The interplay between how states regulate insurance compared with how federal bodies move on this will be a pivotal one to watch and ultimately signals a potential conjoining of the anti-ESG debate with climate-related financial regulation.

Crystallization of climate related financial regulation in the US is one of the opportunities opening up as a result of the anti-ESG movement. A broader range of such opportunities must be the subject of a further paper.

Box 1. Main types of anti-ESG bills

Anti-screening (so-called “anti-boycott”): prevent government entities from doing business with companies that impose fossil fuel or other ESG screens. Proponents inaccurately characterize as “economic boycott” many screens investors adopt to manage climate-related financial risk (e.g., screens to limit investment in fossil-fuel companies without adequate transition plans or involved in building new fossil fuel infrastructure).

Restriction of ESG factors (aka fiduciary duty): tells companies and financial institutions ‘you cannot use ESG factors’. Frequently refers to allowing only ‘pecuniary’. e.g., monetary factors, which they self-define as not including any E, S, G (or political) considerations.

2. Anti-ESG: who, doing what to whom, and how

ESG is the consideration of environmental, social, and governance factors in operations. This will manifest differently for different actors. For a financial actor, ESG can be integrated in the investment process, risk management, or engagement with companies. For a non-financial corporate actor, ESG can influence how a supply chain is structured. ESG was birthed by, and for, financial actors with the phrase originating from the 2004 report ‘Who Cares Wins’, written for financial stakeholders at the behest of the UN Global Compact. Since then, it has evolved to be used by non-financial corporates. Anti-ESG is primarily a Republican political movement in the US which seeks to reduce or eliminate the usage of these factors by financial, and increasingly non-financial, corporates.

The US anti-ESG movement is both a substance and political campaign. A primary motivation for the movement is to preserve or increase funding to sectors with traditionally poor ESG credentials, e.g., fossil fuels, firearms, mining, timber, agriculture, and livestock farming. These industries represent a major donor base for Republicans, which is why politicians continue to push these bills despite lacklustre voter interest. 5 As important, however, are political objectives like scoring points in culture wars and raising the profile of conversative lawmakers. These dual objectives lead to inconsistency within the movement but have not diminished its appeal among Republicans.

Who is anti-ESG? A grouping of Republican US lawmakers and appointed officials largely from states reliant on industries such as coal, oil and gas, agriculture, lumber, and mining. Notable organisations which collectivise anti-ESG action include, but are not limited to, the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) and the State Financial Officers Foundation (SFOF). 6 We wrote about these organisations in our previous paper The US discovers its climate policy: a holistic assessment & implications. 7 These organisations have pushed the anti-ESG movement forward through lobbying, policy development, and litigation. In short, ALEC crafts anti-ESG laws which are mobilised and politicised by SFOF and other ad hoc groupings of Republican states.

What are they doing? The anti-ESG toolkit includes legislative, political, administrative, and legal instruments. Anti-ESG bills are proposed and voted on by state legislators. Investigations carried out by attorneys general currently target asset managers, banks, pensions, and insurance companies. Congressional committee hearings are employed to create political pressure. Inquiries and investigations are also used as a form of legal harassment. An example of this is the use of Civil Investigative Demands (CID) to ask for all internal and external communication from financial institutions related to ESG. This is an effective scare tactic against companies averse to publishing their internal communication on ESG even if the eventual case might be won. The point of these investigations and inquires is more about creating a hassle, or chilling effect, than finding actual legal harms.

While we have not depicted it in the Figure 1 flow chart, it is worth noting that a major avenue for blocking federal regulation is judicial challenge. Given it is easy to exercise and given the composition of the courts, judicial challenge is a substantial threat to ESG.

Box 2. Punishing action (not all are used simultaneously by states)

Mandate divestment: Requires state pension plans to divest from any funds managed by financial institutions who incorporate ESG considerations broadly or who are deemed to “discriminate” against certain industries based on ESG factors.

Alter investment and voting criteria of state assets: Aims to “protect” state assets (particularly state pension funds) from ESG by banning ESG considerations in public investment and voting decisions.

Exclusion from public contracts: Restricts the ability of companies engaging with ESG practices to do business with state governments. Mainly done through anti-screening bills whose proponents inaccurately refer to them as “anti-boycott” bills. This term is misleading since the financial firms being targeted are not consumers boycotting companies for moral or political reasons, but investors seeking to manage climate-related financial risk. Provisions in these bills typically require companies that contract with the state to include contractual clauses in which they commit to continue investing in fossil fuels and/or commit not to restrict investment in certain industries during the duration of the contract.

Fundraising restrictions for state entities: Banning the issuance of ESG-related liabilities such as green and sustainability-linked bonds by state and municipal entities.

Threat of litigation: Largely focused on the violation of antitrust regulation. An argument is that participation by companies and investors in voluntary coalitions with net zero targets like GFANZ amounts to collusion and unfair competition practices. The antitrust threat has been a successful tactic in dissuading companies from cooperating with each other.

Slow blocking new rulings: Introduction of bills asking state legislative bodies, treasurers, or attorneys general to review the constitutionality of federal executive orders and actions concerning ESG climate-related financial regulation. If the state finds a federal action to be unconstitutional, the bill allows the state to prevent enforcement and implementation.

Federal agencies are also facing opposition in implementing ESG-related regulation. For example, the Department of Labor’s 2022 rule clarifying the ability of fiduciaries to consider ESG factors in ERISA private pension plans, was challenged via the Congressional Review Act (CRA)—with the CRA resolution passing with a narrow bipartisan margin before being vetoed by President Biden in March 2023—and is subject to ongoing judicial challenge.

Who are the targets? Financial institutions, voluntary climate organisations, US federal agencies, and non-financial corporates.

Non-financial corporates are primarily targeted through public contracts. For example, in Alabama, corporates that ‘discriminate’ based on ESG factors can no longer do business with the state.8 Energy companies are also targeted. In Texas, public investments are restricted from companies that discriminate against the fossil fuel industry,9 a bill that can potentially be stretched to impact other sectors besides energy. Also, the ambiguous language used in many bills raises the concern that legal subjectivity opens the door for targeting non-financial corporates.

Non-financial corporates may also be targeted indirectly. There is an increasing trend of corporates muting their ESG efforts to avoid being dragged into political turmoil.10 Proxy voting companies are also targeted, with a clause preventing them from raising or supporting ESG matters at company general meetings.

What is the purpose? Changing behaviours such as preventing the incorporation of ESG factors in financial decisions and screening of/decreased investment in industries such as fossil fuels. This is done using (or misusing) definitions of different legal concepts including fiduciary duty, antitrust, and materiality.

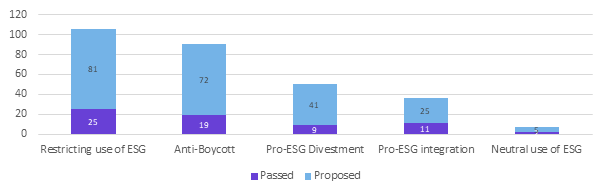

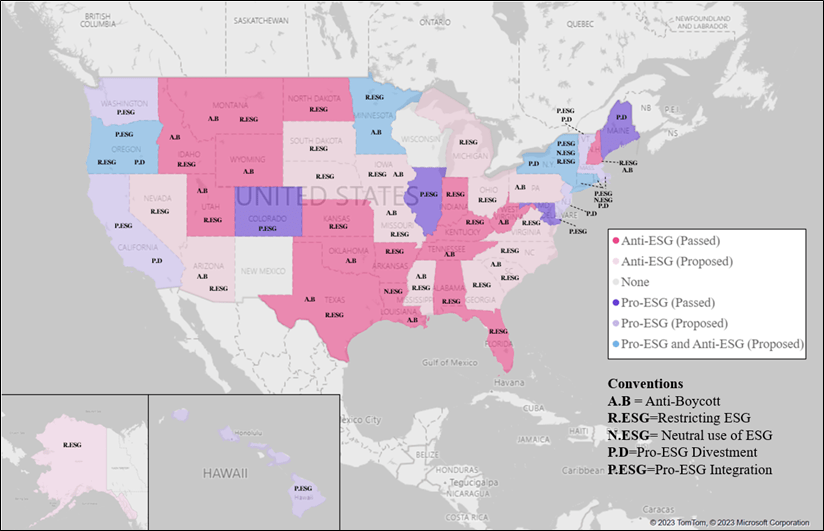

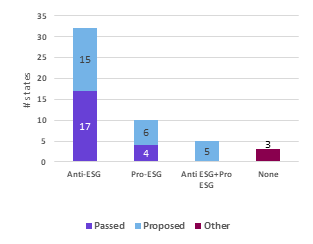

Figure 2 shows the number and breakdown of types of bills, both anti- and pro-ESG and Figure 3 shows a map of the U.S. with a state-by-state analysis of legislation.

Figure 2 Common types of proposed bills

Source: Ropes & Gray State Initiative Tracker as of 09/06/2023

Figure 3 The state of ESG and anti-ESG in the US

Source: Ropes & Gray State Initiative Tracker as of 09/06/2023

Note: (1) Includes legislation passed since 2021 (2) Includes legislation that has been approved by the state’s legislature (3) Classification of bills as per Ropes & Gray State Initiative Tracker.

3. Collective engagement and proxy voting

The anti-ESG movement has also targeted collective engagement bodies and voluntary alliances that pursue common ESG objectives, such as mitigating climate-related financial risk. A favoured target of anti-ESG is an organisation called Climate Action 100+. With 700 signatories and more than USD 68 trillion assets under management (AUM), CA100+ is a collective platform which engages with the world’s largest polluters to encourage them to align with net zero by 2050. Another favoured target is the Glasgow Net Zero Financial Alliance (GFANZ), a global coalition of financial institutions who have voluntarily committed to accelerate the decarbonisation of the economy, and its affiliated alliances such as the Net Zero Insurance Alliance (NZIA).

As on its own, any given company might struggle to affect change at scale, alliances pool many companies together for a common cause. Another way to frame this is that these alliances address collective action problems. Weakening these bodies is central to the anti-ESG movement. To that extent, members of Congress have sent letters to these initiatives requiring them to hand over documents and communications.11 State Attorney General offices have launched legal investigations against some of their members accusing them of breaching their fiduciary duties and antitrust (e.g., Louisiana).12 Utah has even passed a law that could make joining this organisation and others like CA100+ illegal.13 These anti-ESG actions create litigation like processes that result in hassle and costs to firms. As a result, it will be natural for some companies to back away from voluntary alliances rather than comply with a civil investigative demand or subpoena that may be threatened.

Anti-ESG has also impacted engagement by restricting the inclusion of ESG factors in the exercise of shareholder rights such as proxy voting, in the states where the law is active. Some of the states that have included in their bills provisions that limit proxy voting include Florida, Indiana, Utah, West Virginia, and Kentucky.

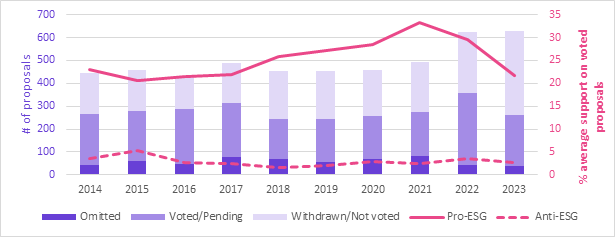

Data by the Sustainable Investments Institute shows a significant decrease in support for pro-ESG shareholder resolutions over the last year and a half. Although the number of ESG-related proposals (both pro- and anti-ESG) has increased,14 support for them, has waned (see Figure 4). The decrease in support for pro ESG-related proposals has been far greater than for anti-ESG. However, this can be attributed to a number of reasons. For example, climate-related proposals are becoming less focused on disclosure and more focused on implementation and transition plans, making them harder to digest for some shareholders. Also, the short-term energy market conditions might also have pushed some shareholders to ditch proposals to ditch fossil fuels. The anti-ESG movement might be only one of these contributing factors.

Figure 4 ESG shareholder proposal outcomes

Source: Sustainable Investments Institute (2023), as cited in Financial Times (2023) Investors pull back support for green and social measures amid US political pressure.

Note: A proposal can be withdrawn for various reasons including a company voluntarily committing to do something to address the issue that the resolution is trying to impose.

4. Who is ‘winning’?

Here we look at more indicators, in addition to the above showing slowing support for ESG-related shareholder proposals. On the surface, anti-ESG is notching gains but not necessarily on areas of substance.

More US states are passing anti-ESG policies, and the pace of their legislation is accelerating. Figure 5 shows that 17 states have passed anti-ESG legislation into law and a further 15 states have proposed anti-ESG bills.15 This compares with just 4 states who have passed pro-ESG laws and 6 states who have proposed pro-ESG bills. The pro-ESG variety of bills either require the consideration (integration) of ESG factors into investment decisions or require divestment from certain industries (e.g., fossil fuels) by a certain date. 5 states have proposed both anti- and pro-ESG bills and only 3 have taken no stance.

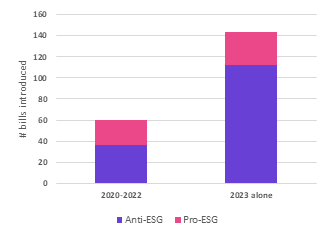

The bulk of ESG legislation is dominated by the anti-ESG variety. In 2023 alone, 112 anti-ESG bills have been proposed, although some research puts this number as high as 16516 depending upon how ESG is defined. There have been 31 pro-ESG bills by comparison. This means at least triple the number of anti-ESG bills have been proposed in 2023 compared to the previous three years combined (see Figure 6).

Figure 5 Most states are anti-ESG

Figure 6 The number of anti-ESG bills has exploded

Sources: 5. Ropes & Gray State Initiative Tracker as of 09/06/2023 6. Debevoise & Plimpton State-level ESG investment Developments Tracker as of 16/05/2023

The legislative process does not fully represent state action on ESG, especially regarding pensions, as some states have been able to craft policy without passing legislation. For example, Republican state treasurers in Utah, South Carolina, Florida, Arizona, Louisiana, and West Virginia have divested state funds from BlackRock over its ESG policies, even in the absence of state laws compelling them to do so. Governors have also gotten involved, such as New Hampshire’s Chris Sununu, who signed an executive order barring the state retirement system from investing solely based on ESG factors.

The pro-ESG movement has also made use of executive powers. Treasurers in states like Oregon, Nevada, and Connecticut have proposed a range of actions, including responsible gun policies, pension decarbonisation plans, and divestments from fossil fuels and assault-style weapons manufacturers. State investment councils in Oregon and New Mexico both formally adopted ESG considerations into their policies, while other state pension boards have announced net zero targets and active divestment campaigns. The most notable of these is at the municipal level, with the NYC Comptroller announcing a 2040 net zero target for two out of five state pension funds with $172.6 billion in AUM.17

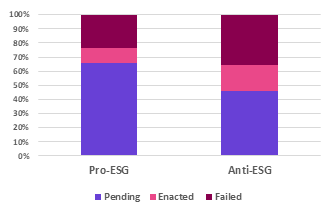

The anti-ESG movement has been less successful in consolidating its legislative attack, as seen in the relatively large failure rate of bills. Since 2020, ~36% of anti-ESG bills have failed compared with the ~20% failure rate of pro-ESG bills (Figure 7). If the amount of anti-ESG bills is as high as 165 as some attest, this success rate for anti-ESG bills is even lower, hovering around 16%. This suggests that, whether by design or not, the anti-ESG strategy operates on a quantity over quality basis regarding bill construction. Republican lawmakers likely see as much, or more, political gain from proposing bills as from constructing a well-thought-out piece of legislation.

Figure 7 The failure rate of anti-ESG bills is higher than pro-ESG

Legal opinions abound on the substance of anti-ESG legislation. A useful legal analysis describes the ALEC-drafted so-called ‘boycott’ and ‘fiduciary’ bills (what we call ESG restriction bills), which have been used in a plug-and-play fashion across states, as ‘well-funded’ but ‘extremely clumsy legal attacks’.18 According to this analysis, the bills are clumsy because they would create a ‘fiduciary trap’ for investors. As a result, trustees, their advisors, and others would find themselves unable to comply with the ALEC bills without violating existing state law, federal law, or both.

Furthermore, gaps and ambiguities would generate substantial compliance risk for fiduciaries. This would in turn diminish the appeal of serving as a fiduciary or provide services to public pension funds and could increase liability and insurance costs for funds on top of increased investment fees and reduced returns. In the end, the aforementioned analysis argues that ‘the bills would harm the very people they purport to serve: taxpayers and fund participants and beneficiaries, who will face higher costs, lower returns, and greater legal risks in states where the ALEC bills become law.’ 19

These risks are making even Republican states reconsider adopting anti-ESG legislation. A case in point is Indiana, where a study by the Indiana Legislative Services Agency (LSA) estimated that HB 1008, a proposed bill barring asset managers who consider ESG factors from managing state pension plan assets, would result in USD 6.7 billion in lost returns over 10 years. The bill was subsequently watered down to exempt private market funds and provide several avenues for retaining existing asset managers. The inclusion of these loopholes caused LSA to revise its estimate to only USD 5.5 million in lost returns over the next decade, and the bill later passed with this seemingly acceptable cost. Box 3 lists many other examples.

Box 3: Reasons why anti-ESG legislation is being opposed, watered down, or failing

1. Lost returns for state retirement plans

• Indiana passed a watered-down version of a bill (HB 1008) that cuts ties with banks that consider ESG factors after it was estimated that it could cut $6.7bn from investment returns of the public pension system over a decade .

• Kansas legislative research estimated that the pension system would lose $3.6 billion over the next 10 years if the state enacts a proposed “anti-boycott” bill (SB 244).

• Kentucky County Employees’ Retirement System (CERS) trustees informed the state treasurer that CERS is not subject to a state law mandating divestment from entities that “boycott” energy companies, claiming that doing so would be inconsistent with their fiduciary duties.

• Oklahoma enacted an Energy Discrimination Elimination Act (SB 1572), blacklisting investors that are accused of discriminating against fossil fuel companies. The Oklahoma Public Employees Retirement System estimated that the bill could cost the state’s second-largest pension fund at least $9.7 million.

• Texas proposed a bill (SB 1446) that would force pension funds to divest from asset managers if they consider ESG factors in their investment strategies. The Texas County & District Retirement System estimated that a restriction of certain asset managers because of the bill could cost upwards of $6 billion over the next 10 years.

2. Higher borrowing costs

• Texas is expected to incur $300-$500m of additional borrowing costs during the first eight months alone after enactment of its two “anti-boycott” bills (SB13 and SB19), according to a recent academic study.

• In January 2023, Econconsult Solutions Inc. published a study that extends the above Texas methodology to other states. The study concludes that the implementation of similar “anti-boycott” bills in Kentucky, Florida, Louisiana, Oklahoma, West Virginia, and Missouri would increase interest payment costs by $264-$708m over 12 months. Florida alone would bear $97-361m.

3. Loss of contractors

• Wyoming legislators voted down a proposal that would restrict government entities from doing business with banks, investors or companies that consider ESG factors (SF159 and SF172). Legislators and the state treasurer expressed fears that the bills (both ”anti-boycott”) defined ESG so broadly and subjectively that they could end up restricting contractual relationships with a vast majority of businesses.

4. Punitive costs from breaking contracts

• Wyoming State Treasurer, Curtis Meirer pointed out that Wyoming has a 10-year private equity contract with BlackRock and that breaking it could be expensive and difficult for the state.

5. Financial industry pushback

• Kentucky state attorney general Daniel Cameron was sued by the Kentucky Bankers Association (KBA) after he issued subpoenas and civil investigative demands against several large banks relating to their involvement with the Net Zero Banking Alliance (NZBA). The KBA accused Cameron’s demands of “creating an ongoing state surveillance system.”

• New Hampshire passed a bill (HB 457) that precludes investors from considering climate change (systemic factors) but was opposed by the New Hampshire Bankers Association, who warn that it could prevent them fulfilling basic loan criteria.

• A recent investigative report found that industry lobbyists mounted opposition to anti-ESG bills in at least 17 states

6. Negative impacts on fossil fuel companies trying to diversify their assets

• North Dakota voted down legislation that would prohibit doing business with investors engaging with ESG policies (HB 1347). In the pushback against the bill, opponents argued that the state energy industry’ ability to expand carbon capture technologies relies on external capital, which would be limited by the bill.

• Wyoming State Treasurer pointed out that passing the “Stop ESG-Eliminate economic boycott act” (SF 159) would potentially have unintended consequences, such as prohibiting investments in Peabody Energy, the state’s largest coal mine operator, as well as several large oil and gas companies who are looking to diversify their energy investments.

Concluding that the anti-ESG movement is ‘winning’ purely from calculating the number of bills or number of states is a flawed methodology. Pro-ESG executive orders must be considered as must the content of enacted legislation which, in many cases, is watered down to the point of being ineffectual.

Disruptive anti-ESG legislation is galvanising the diverse scope of actors who would be adversely affected by its implementation. Trade unions, pension holders, and banking associations across states all stand to be negatively impacted by proposed anti-ESG legislation, not just asset managers, and are all taking action against it, as evidenced in Box 2.

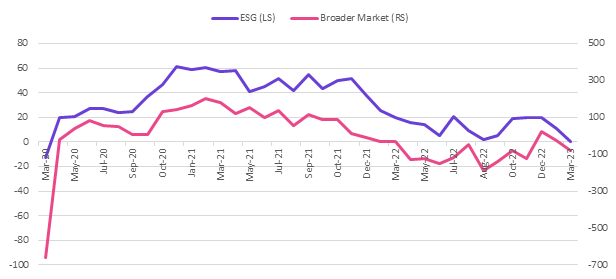

Financial fund flows are also an indicator of the anti-ESG movement’s impact. The data reveals declining flows into ESG-related public financial product (Figure 8). The spread between global ESG flows and broad market flows has now compressed to being near equivalent for the first time in 4 years. This data is only available for public listed funds. Private equity and unlisted funds also allocate to ESG products, but reporting requirements are not as strict, thus obscuring the full picture.

Figure 8 Change in global monthly ESG flows vs broader market flows $bn

Source: Morningstar (2023), as cited in Morgan Stanley (2023) Sustainable Trends: ESG Funds Experience Modest Inflows, as of 03/05/2023

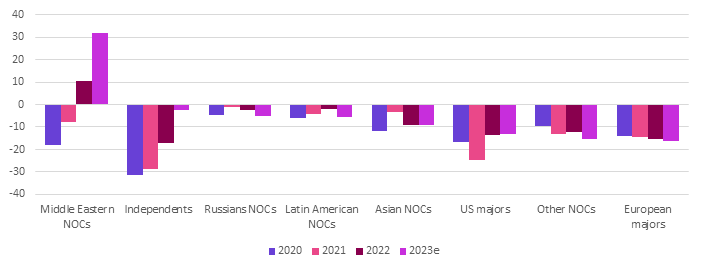

A drop in the number of sustainability fund launches paints a similar story. Launches peaked in 2021. Data for the first four months of 2023 indicates fund launches will continue falling this year. Annualising the current rate would imply the number of new sustainable fund launches would roughly equate to levels last seen in 2017 or even 2016 (Figure 9).

Figure 9 Number of Sustainability Fund Launches

Source: Morningstar (2023), as cited in Morgan Stanley (2023) Sustainable Trends: ESG Funds Experience Modest Inflows, as of 03/05/2023

While notable, we hesitate to infer a causal link between this public fund data and anti-ESG efforts. There are other factors that are likely to be having an impact such as an increase in regulatory scrutiny on greenwashing in Europe (where a vast majority of ESG funds are located), cyclical energy prices (which make fossil fuel companies generate high but temporary revenues), higher interest rates (which disproportionately affect growth stocks like tech companies who score well on ESG metrics), and efforts by fund managers to tighten their own definitions of ESG integration.

5. Capital flows, a real economy impact of anti-ESG

We are sceptical that redirection of equity flows resulting from anti-ESG has a significant real-world impact on the topics anti-ESG are wishing to influence, e.g., climate transition. This is because the universe of ESG-related funds in the location of strongest anti-ESG sentiment, America, is very small. The EU currently holds 85% of global ESG AUM (Figure 10). In the EU, ESG funds represent around 30% of total regional AUM while in the US this proportion is around 1%.

Figure 10 The US ESG accounts for a minuscule part of regional AUM

Source: Morningstar (2023), as cited in Morgan Stanley (2023) Sustainable Trends: ESG Funds Experience Modest Inflows, as of 03/05/2023

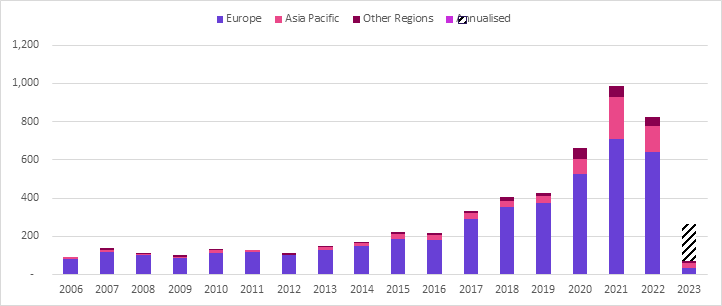

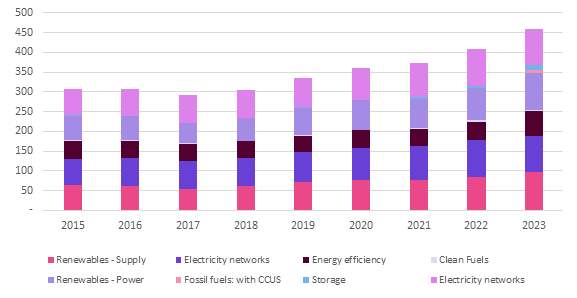

A significant real-world impact would occur if anti-ESG measures successfully redirected capital flows into fossil fuel industries instead of clean energy industries. We do not see evidence of this. Figure 11 shows clean energy investment rising strongly in North America in the last years. Other regions are following a similar pattern. At the same time, capital directed towards oil and gas investments has been decreasing, except for in the Middle East (Figure 12). One can see why the anti-ESG proponents are concerned about both future availability and cost of capital for high carbon energy projects.

Figure 11 Clean energy investment flows in North America $bn

Source: IEA (2023). World Energy Investment 2023, as of May 2023

Figure 12 Change in upstream oil and gas investment relative to 2019, $bn

Source: IEA (2023). World Energy Investment 2023, as of May 2023

While capex plans are increasing for fossil fuels projects as a result of higher prices in 2023, investment will still be 35% below 2014 levels.20 Furthermore, the hurdle rate of oil products has risen from 10% in the 2004-14 period to 15-20% recently. This higher hurdle rate, which tracks the cost of capital, equates to a required break-even price of $80/barrel of oil on a new project vs. $70/barrel previously. An enormous effort would be needed by anti-ESG state lawmakers in the US to redirect enough capital to overcome this structural shift in cost of capital for fossil fuel projects. This is an area to monitor, as would the movement of financial fixed income flows which we have not looked at here.

Additionally, on the demand side, economic forces now include historically unparalleled and coordinated industrial policy support for clean energy not only in China but also the US, EU, Canada, Japan, Australia, India, and other countries.

This does not rule out micro-level changes in cost of capital for states wishing to swim against the tide of market forces. In Florida, the ESG bond ban may increase borrowing costs as ESG bonds are often a cheaper source of capital for renewable energy projects. Similarly, Arkansas’ restriction on using certain financial institutions will likely impact the borrowing cost of the state as competition decreases, raising rates further – a cost likely passed on to the taxpayers.21

6. Case study: Florida and Texas anti-ESG bills

Both Florida and Texas passed anti-ESG legislation in the last two years, but the nature of the legislation and the political motivations differ.

Florida passed a sweeping bill focused on restricting ESG integration in the investment process. This bill was notable for its aggressive features, including provisions that had not been seen in other states thus far, such as its restriction on the issuance of ESG bonds. No industry was cited in the legislation as requiring protection, suggesting a political rather than economic motivation.

Texas, on the other hand, has focused on pushing forward so-called “anti-boycott” bills that protect state industries which are strategic either for their economic value (e.g., fossil fuels) or cultural significance (e.g., firearms). The Texas bills were the first of their kind and among the earliest bills passed in the anti-ESG movement. Although Texas has also introduced bills that restrict the integration of ESG factors into investment decisions, they follow a similar model to those passed in other Republican states. Relatedly, Texas legislators attempted to pass significant regulation designed to disadvantage renewable energy at the expense of fossil fuels.22 This is uncharacteristic for Texas’ famously free market and low regulation energy grid but perfectly aligns with an anti-ESG agenda designed to be economically protectionist in favour of the fossil fuel industry.

Table 1 Comparing anti-ESG bills in Florida and Texas

| State | Florida | Texas |

| Name | House Bill 3 | Senate Bill 13 + Senate Bill 19 + Senate Bill 1446 |

| Bill types | Restrictions to ESG integration | “Anti-boycott” (energy and guns) + Restrictions to ESG integration |

| Key provisions | Restrictions to ESG integration Bans ESG considerations in public investment decisions and financial discrimination based on ESG factors · Bans the issuance of ESG-related bonds at the state and municipal levels · Mandates asset managers to introduce disclaimers in all external communications that their views do not reflect the views of Florida Bans state entities from doing business with ratings companies whose ESG ratings negatively impact Florida | “Anti-boycott” (energy) · Prohibits investment in financial companies that boycott energy companies (explicitly mentions those that rely on fossil fuel-based energy) · Mandates the state treasurer to create a list of restricted financial institutions suspected of boycotting energy · State investment entities must divest from institutions on this list if they cannot prove that they do not boycott energy companies · Prohibits state contracts with companies that boycott energy “Anti-boycott” (firearms) · Prohibits contracts with companies that “boycott” firearms manufacturers Restrictions to ESG integration Requires state pension funds to consider only material financial factors in investment decisions and voting |

| Main state economic activity | Nothing in the bill references protection of a specific industry (the main industries in Florida are real estate, tourism, and agriculture | · Energy is a major industry alongside with aerospace, manufacturing, and IT · Energy sector worth $172bn · Employs >250,000 people Holds 28% of the country’s oil refining capacity |

| Messaging based on press release when the bills passed | · Focus on putting the interests of hardworking people above corporate elites Connects ESG factors to broader Republican agenda topics like firearms and migration control | · Focus on protecting fossil energy jobs and the state’s economy Focus on local politics and narrative of “Putting Main Street over Wall Street” |

| Political motivation | Unify the Republican front in the so called “culture wars” to strengthen Gov. DeSantis’s presidential campaign | Protect the future financial sustainability of the state’s strategic industries and push back against outside influence |

7. Fire or smoke? Antitrust and fiduciary duty

Antitrust and fiduciary duty are commonly cited by anti-ESG actors during legislative and legal manoeuvres.23

Clarification of antitrust policy as it pertains to climate- and ESG-related cooperation is more advanced in the EU and UK compared with the US.

Antitrust policy is designed to prevent companies from adopting anti-competitive behaviour or abusing dominant positions at the expense of consumers. Anti-ESG actors have contended that corporations and financial institutions coordinating to set voluntary emissions-reductions targets is a violation of antitrust policy. Alleged antitrust violations are an effective legal threat; a 2020 report by the OECD cites a survey suggesting that 60% of businesses “had shied away from cooperation with competitors for fear of competition law”.24

Anti-ESG actors portray collective action for climate as collusion designed to choke off funding for fossil fuels. The effectiveness of this accusation is seen in 13 global insurance companies bowing out of the Net Zero Insurance Alliance (NZIA) and friction amongst members of the Global Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ).

In part because of anti-ESG actions, UK and EU policymakers are clarifying antitrust policy as it relates to cooperation on climate and ESG more broadly. The UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) published guidance in February 2023, citing environmental sustainability as a major public concern and announcing that the CMA is keen to ensure that businesses are not unnecessarily or erroneously deterred from lawfully collaborating in this space due to fears about competition law compliance. The government expressed that this is particularly important for climate change because industry collaboration is likely to be necessary to meet the UK’s binding international commitments and legislative obligations to achieve a net zero economy.25

The EU has issued guidelines dealing with competition and how it relates to ESG factors, including climate. According to the guidelines, which will come into effect in July 2023, sustainable development is a core principle of the Treaty on European Union and a priority objective’.26 These guidelines include six (6) criteria which, if met, provide a safe harbour for financial and corporate actors cooperating on climate goals.

No equivalent clarity of antitrust policy as it relates to climate or ESG exists in the US. Table 2 lays out why it is harder to get clear guidance on the specific inclusion of climate-related antitrust considerations in the US relative to the EU and UK. In the US, antitrust is often a criminal offense and can be prosecuted under federal and state statutes. Political motivations can direct action as well. Under President Trump, the DOJ sought to prosecute four auto manufacturers for complying with California fuel standards (ultimately the investigation was dropped). Also in the US, direct litigation can result in very large fines of up to 3 times deemed damages.

The oversight of antitrust in the US is more complex and fragmented. Although the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) have authority at the federal level, each state develops their own antitrust laws. Also, the US has a common law system, in which decisions on antitrust are determined by courts deciding cases and providing the legal basis for future decisions. This leaves decisions more exposed to practical interpretation.

Politics can also play into US judicial rulings depending upon political leaning of the district or judges, which is a system wide aspect of judicial politics and not just specific to antitrust. The extreme example of this is the Supreme Court has a Republican supermajority that has issued a number of recent rulings curtailing the power of the federal administrative state. For example, the ‘Major Questions Doctrine’27 used to limit the EPA’s ability to regulate greenhouse gas emissions28 could be applied to a wide range of decisions constraining executive power.

Table 2 Comparing the governance of antitrust in the US, UK, and the EU

| US | UK | EU | |

| Governing body | Federal Trade Commission, Department of Justice | Competition and Markets Authority | European Commission |

| Enforcement system | Criminal and civil (DOJ), administrative (FTC) | Criminal and administrative | Administrative |

| Penalties | Fines (as large as triple damages) and custodial | Fines and custodial (for cartel offences) | Primarily fines at EU and member state level |

| Sub-regional governance | Yes – state level antitrust laws | No | Yes – member state level antitrust laws |

| Relevant considerations | Importance of court rulings and precedents, politically driven agency investigations | Concurrent powers held by sectoral regulators, e.g. Ofgem (energy), FCA (financial services) | Protecting the single market, state aid |

| Regulatory allowance for cooperation on climate | No | In process | In process |

It is somewhat ironic how we have come full circle in antitrust argument. Anti-ESG campaigners use the concept of antitrust now to protect fossil fuel companies, when its most famous early usages were to break up the Standard Oil Company monopoly in 1911 under the Sherman Act.29 Regardless, our conclusion on the concept of antitrust and climate coordination is that investors will find more clarity in the EU and UK than in the US.

UK and EU address ESG in fiduciary duty while the US is again, behind. Additionally, the whole matter is more subjective than antitrust.

Fiduciary duty, broadly, is the legal responsibility to act in the best interests of another person or party rather than oneself. While the definition of fiduciary duty varies by jurisdiction and application, the general principle requires that material topics need to be considered when making decisions. Materiality involves the requirement to consider and report any piece of information which might reasonably be expected to influence decisions.

Similar to antitrust, the US again trails the UK and EU when it comes to clarifying treatment of investment use of ESG factors. The shaded areas in Table 3 highlight some core differences in these jurisdictions.

Table 3 Comparing ESG and the concept of fiduciary duty in the US, the UK, and the EU

| US | UK | EU | |

| Legal framework | Defined by law. Open to practical interpretation. Ruled by common law based on legal precedents | Defined by law. Open to practical interpretation. Ruled by common law based on legal precedents | Defined by law at member state level. Ruled by civil law based on codified rules and regulation |

| Historical interpretation | Broad definition: The Prudent Person Rule | Narrow definition: no conflict and no profit duties | Varies per member state |

| Regulatory ESG framework | No federal regulation | Regulatory requirements (country level) | Requlatory requiremnets (EU and MS level) |

| Macro ESG beliefs | Highly fragmented and politicised | Growing consensus | Growing consensus |

| ESG mandate | Hinges on the interpretation of fiduciary duty | Formal and informal integrated within fiduciary duty | Formal and informal integrated within fiduciary duty |

| Pension funds – example | Private pension: DOL ESG ERISA rule. Public pension: highly politicised state ESG regulation | ESG regulation and disclosure covers pension funds. Fiduciary duty varies per type of pension fund | Overarching ESG requirements for pension funds in each member state |

The EU and UK have already introduced statutes and guidance to clarify whether ESG can and should be considered financially material in investment and businesses decisions. For example, in the UK, guidance by the Law Commission since 2014 has specified that ESG factors can be considered financially material. In the EU, various pieces of regulation have already clarified that sustainability factors must be considered in investment decisions, (e.g., MiFID II, Solvency II) and different sustainable finance frameworks have been created to promote transparency and standardisation of ESG investing broadly (e.g., EU Taxonomy, SFDR).

In the US, there has not been systematic clarification of fiduciary duties as it relates to ESG investing and integration, providing space for Republican state actors to interpret the concept in line with their objectives. For example, while the DOL’s ERISA clarifies that fiduciaries can consider ESG factors when selecting investments, the regulation is limited to the context of the ERISA retirement plan. Moreover, as we have written elsewhere, relative to the EU the US lags in developing policies to increase transparency of ESG investing (e.g., SEC’s proposed ‘Names Rule’,30 and ‘ESG Investment Practices Rule’31 ) and such rules are likely to face implementation challenges.32

Anti-ESG lawmakers promote a contradictory definition of fiduciary duty and materiality regarding ESG. They assert that ESG factors are inconsistent with fiduciary duty and materiality and thus should be excluded in favour of “non-pecuniary factors” (non-monetary factors) and further self-define ESG as being non-pecuniary. This despite existing federal securities laws and Supreme Court precedent on fiduciary duty which says that investors are obliged to consider all aspects that have the potential to affect long-term financial risks and returns as material. One would think that scientifically proven climate change meets this definition. Critically, are investors supposed to ignore companies who treat climate change as material to their business and should they also ignore federal law if it contradicts new anti-ESG state law?

Thus, the legal trap. The aforementioned legal analysis points out that, under anti-ESG definitions, an investor who considers climate risk in their investment decisions would be committing an illegal act because climate change is an environmental factor that falls under their “non-pecuniary” definition, even if this presents a discrepancy between state and federal interpretations.

It is likely that those behind anti-ESG are aware of these, and other, contradictions in the bills. Even if investors win the ultimate legal challenge, they are still drawn into highly politicised and public inquires, the result being extra legal costs and complexity for the investor at a minimum. Some investors are finding the risks too high, the new scenario too complex, which results in disengagement.

8. Insurance battle ground & climate-induced insurance market contagion

It is essential that financial and corporate actors individually price climate in their investment and business models, irrespective of the anti-ESG wildfire. Recently, two significant events occurred simultaneously in the insurance industry. 13 of 30 major insurers announced their exit from the NZIA as a direct result of anti-ESG litigation threats33 while, around the same time, 5 (different) major insurers across a variety of US states announced a withdrawal or pause on offering new contracts, citing the impact of climate change as a primary reason.34 The exits from NZIA occurred directly after 23 Republican US state attorneys general issuing a letter to the members of the NZIA threatening antitrust allegations and requesting documents relating to their participation and internal communications.35

Despite this publicity win for the anti-ESG movement, many insurers doubled down on their sustainability commitments in their exit statements. AXA and Allianz, two of the most high-profile exits, affirmed that their net zero strategies remain unchanged, with Allianz stating its continued support for the Net Zero Asset Owners Alliance (NZAOA). The CEO of Munich Re, the reinsurance giant, reassured the public after their exit that the company’s climate commitment is “unwavering”. Some former members went even further. On the day of its exit, SCOR unveiled a more restrictive fossil fuels policy that stated the global insurer will no longer cover the development of new gas fields.

Collective action does not replace individual action, and insurance companies know they must price ever-increasing climate risk. Over the period from 2020-2022, the increasing frequency of natural disasters combined with inflation in the cost of re-building due to material and labour shortages created a record $275 billion in losses in the US, bankrupted 11 insurers in Louisiana, and rendered 15 insurers in Florida insolvent.36

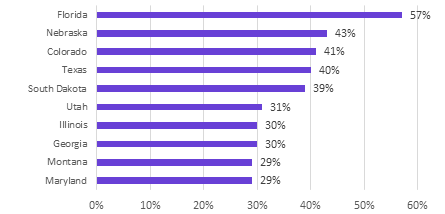

Climate-induced insurance market contagion does not stop here. The exit of these major insurers has contributed to a large spike in home insurance premiums in affected areas (7 out of the top 10 largest increases are in anti-ESG states).

As Florida passes laws restricting the use of environmental factors in investing and state business, its homeowners have seen their insurance premia increase 57% since 2015, nearly triple the national average of 21% (Figure 13).

Between May 2021 and May 2022, 90% of U.S homeowners saw an increase in their home insurance premiums. Areas prone to severe weather like Arkansas, Texas, and Colorado saw steeper increases than the average.37

Figure 13 Average increase in homeowners insurance premiums since 2015 – 7 of top 10 are anti-ESG states

Source: LexisNexis Risk Solutions 2023

This dynamic has driven a huge increase in the policies written by state-run insurers as homeowners get priced out of private coverage or lose access completely. In Florida, Citizens Property Insurance Corp, a state sponsored insurance company, saw the number of insured hit a record 2 million people.38 Governor Ron DeSantis made the startling comment that Citizens is not even solvent.39 Also, due to the opaque inner workings of the US mortgage securitisation engine, after a natural disaster occurs, there is a perverse incentive for lenders to approve mortgages in that area that can be securitised by government-sponsored entities (GSEs).40 This results in a transfer of climate risk into the mortgage securitisation market and onto the balance sheets of the GSEs Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Additionally, banks are increasingly faced with exposure to uninsurable segments of the economy, notably in the property and homeowner market. According to NOAA: ‘In 2022, the U.S. experienced 18 separate weather and climate disasters costing at least $1 billion. That number puts 2022 into a three-way tie with 2017 and 2011 for the third-highest number of billion-dollar disasters in a calendar year’.41 Coupled with the increasing frequency and severity of climate hazards, these dynamics could result in large, unexpected losses among unsuspecting financial actors.

For example, the Bank of England’s 2021 Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario (CBES) found that banks’ planned climate risk management strategies included reliance on insurance that the insurers would not be willing to underwrite under the scenarios employed.42 No amount of anti-ESG action can conceal these clearly material variables, but it is unclear what effect this pricing disconnect might have as a countervailing force and driver of policy in the US, which lags behind the EU and UK in implementing climate-related financial regulation.43 Decreasing insurance coverage contributes to an uneven build-up of risk in other parts of the financial system.

These insurance protection gaps and risk transfers highlight the need for climate-related financial regulation.

Divergent approaches to climate-related financial regulation for insurance are emerging across states. For example, while some state insurance commissioners have proactively engaged in climate scenario analysis (CA in 201844 and NY in 202145) and climate risk data collection (15 jurisdictions administered NAIC’s Insurer Climate Risk Disclosure Survey in 202146), other states are seeking to restrict insurers incorporation of climate risk. For example, Texas has just passed into a law Senate Bill 833 which prevents insurance companies from considering ESG policies when setting premiums,47 which presumably includes consideration of climate which insurance companies are citing as material risk factors in setting premiums as above.

While insurers are primarily regulated at the state level, there are important federal authorities that can be employed to monitor and mitigate systemwide risk. For example, in response to President Biden’s 2021 EO 14030 on Climate-Related Financial Risk,48 the Federal Insurance Office (FIO) of the US Treasury Department has collected information on climate-related financial risks in the insurance sector,49 proposed more systematic climate data collection,50 and recently issued a report on ‘Insurance Supervision and Regulation of Climate-Related Risks’ which notes deficiencies in, and makes recommendations for, insurance sector climate risk measurement and state regulatory and supervisory actions to improve climate risk management.51

While FIO is empowered with insurance system monitoring rather than regulation, the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) has the authority to designate non-bank systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs)—including insurers—which brings them under federal regulatory authorities. While no SIFIs are currently designated, FSOC has recently proposed both revised designation guidance52 and a new analytical framework 53 for financial stability risk, which describe climate change as a potential source of systemic risk and thus a potential factor in designation. These broader issues related to climate-related financial systemic risk regulation are a subject for a longer paper.54

For the purposes of this paper and to conclude, the insurance industry case study is an important reminder to see through the smoke of anti-ESG. While some actors wait for the political noise to stop and the regulatory landscape to be clarified before they move forward, others are driven by the prospect of financial risk (and opportunity) to act now. The fragmentation of ESG policy and materiality of climate risk demonstrate the need for more comprehensive climate-related financial regulation.

This research note has been prepared and issued by Kaya Advisory Ltd (‘Kaya’) in accordance with its contract with the intended recipient to whom it is addressed. All intellectual property subsisting in the note is the property of Kaya or its third-party licensors unless otherwise agreed by us in writing. The note is private and confidential and is intended solely for the person(s) to whom it is addressed. Redistribution and dissemination of its contents are prohibited. You must obtain our prior written consent before quoting this research note. To the fullest extent permitted by law, Kaya shall have no liability whatsoever (including, without limitation, in negligence or otherwise) for any decision taken based on information contained in this research note. This research note does not constitute investment research and should not be treated or relied on as such.

This short paper by Brian Hensley, Chris Schenker, Sara Romby and Lara Gutierrez Santander at Kaya Partners, a specialist climate policy consultancy, has been commissioned by the Inevitable Policy Response (IPR). PRI commissionedthe Inevitable Policy Response in 2018 to advance the industry’s knowledge of climate transition risk, and to support investors’ efforts to incorporate climate risk into their portfolio assessments.

The views in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of the IPR research consortium.

IPR is a climate transition forecasting consortium commissioned by the Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI) whose aim is to prepare investors for the portfolio risks and opportunities associated with accelerating policy responses to climate change. The key outputs of IPR consist of the Forecast Policy Scenario (FPS) and the 1.5°C Required Policy Scenario (RPS). Both the FPS and the RPS are intentionally designed to be long-term, running out to 2050 and beyond. Both scenarios assumed emissions rose slightly out to 2025/6 when published in October 2021.

Footnotes

- Leaving aside the nuance of anti ESG vs. pro ESG vs. anti-anti ESG.

- As data compiled by Ropes & Gray, which can be found here. One recently released report from Pleiades Strategy put this figure even higher at 165 total proposed in 2023 as of June 2023. Link

- Pension & Investments (2023). BlackRock CEO Larry Fink says he no longer uses term ‘ESG’. Link.

- Banking Dive (2023). Kentucky banking trade group sues state AG over ESG policy demands. Link.

- Most republicans are unfamiliar with ESG and express no opinion on whether it is good or bad. Gallup (2023). ESG not making waves with American public. LinkMost republicans are unfamiliar with ESG and express no opinion on whether it is good or bad. Gallup (2023). ESG not making waves with American public. Link.

- Besides ALEC, organisations like the Heritage Foundation, the Heartland Institute, and the Foundation for Government Accountability (FGA) have drafted ‘plug and play’ bills used by multiple states. Lobbying efforts have been led by organisations like the Texas Public Policy Foundation (TPPF) and The Opportunity Solutions Project (OSP), amongst others. Besides SFOF, other groupings of financial officials like the Republican Attorneys General Association and the Rule of Law Defence Fund have contributed to push anti-ESG forward.

- The Inevitable Policy Response & Kaya Partners (2022). The US discovers its climate policy: A holistic assessment & implications

- Alabama Senate Bill 261 (2023). Link

- Texas Senate Bill 833 (2023). Link

- South Pole (2022). Net Zero and Beyond: A Deep-Dive on Climate Leaders and What’s Driving Them. Link

- US House of Representatives (2022). Letter addressed to Climate Action 100+. Link

- Washington Times (2023). Louisiana launches ESG probe into major climate fund pushing green investments. Link

- Utah State Legislature (2023). H.B. 449 Business Services Amendments. Link

- Partly thanks to an SEC decision to backtrack on guidance that required companies to exclude shareholder climate proposals that asked them for certain timelines and targets for their greenhouse gas emissions. Link

- Most US states have a bicameral legislature, with a House of Representatives/Assembly and a Senate. For a bill to be passed it needs to be discussed and approved by both chambers of a state’s legislature. Once passed, legislation goes to the governor’s for signature. The governor can veto the bill, but the legislature may have the power to override a veto. A bill that has been signed by the governor is enacted. Bills that are not enacted can be re-introduced, and some states have two-year legislative cycles which enable carrying over legislation for the next year.

- Pleaiades (2023). Right-Wing Attacks on the Freedom to InvestResponsibly Falter in Legislatures. Link

- As of March 31, 2023. Office of the NYC Comptroller: Link.

- Webber, D. H., Berger, D., Young, B. in Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance (2023). The Liability Trap: Why the ALEC Anti-ESG Bills Create a Legal Quagmire for Fiduciaries Connected with Public Pensions. Link

- Ibid.

- Goldman Sachs (2023). Top Projects 2023: Back to growth. Link.

- Climate Wire (2023). States shrug off warnings, plow ahead with anti-ESG laws. Link

- The New York Times (2023). Will Texas Blow Up Its Energy Miracle to Bolster Fossil Fuels? Link

- Note we are not professing a legal opinion, but rather offering a comparison framework between the US, UK, and EU. examples include The Antitrust Attorney Blog (2021). Five U.S. Antitrust Law Tips for Foreign Companies. Link; Bipartisan Policy Center (2021); Comparison of Competition Law and Policy in the US, EU, UK, China, and Canada. Link

- OECD (2020). Climate Change and Competition Law. Link

- Competition and Markets Authority (2023). Sustainability – Exploring the possible. Link

- European Commission (2023). Guidelines on the applicability of Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union to horizontal co-operation agreements. Link

- The Major Questions Doctrine is a narrow interpretation of the statutory delegation of authority to executive agencies, which was used in the majority opinion of the 2022 West Virginia vs EPA case and relates to a longer-standing legal conservative interpretation of US administrative law.

- Supreme Court of the United States (2022). West Virginia et al. v. Environnemental Protection Agency et al. Link

- Supreme Court of the United States (1910). The Standard Oil Company of New Jersey et al. v. the United States. Link

- US Securities and Exchange Commission (2022).Proposed rule: Investment company names. Link

- US Securities and Exchange Commission (2022). Proposed rule: ESG Disclosures for Investment Advisers and Investment Companies. Link

- Kaya (2023) Transatlantic Divergence & Domestic Turbulence: EU & US ESG Policy Landscape Update; Kaya (2023) Climate-Related Financial Regulation & ESG Policy: 2023 EU, UK & US Outlook; Kaya (2023) ESG Regulation for Financial Market Participants.

- Allianz, AXA, Grupo Catalana Occidente, Hannover Re, Mapfre SA, Munich Re, MS&AD, QBE, Scor, SOMPO, Swiss Re, Tokio Marine, and Zurich.

- Allstate, Farmer Insurance, State Farm and United P&C. AIG is reportedly planning to leave multiple states.

- Office of the Attorney General State of Utah et. al (2023). Letter to the Net Zero Insurance Alliance (NZIA). Link

- TMiami Herald (2023). Florida’s home insurance rates rising faster than any state, nearly triple U.S. average. Link

- Policygenius (2022). Home insurance pricing report. Link

- WUFT (2023). Florida residents being dropped by private insurance companies turn to state-backed insurer. Link

- Insurance Journal (2023). DeSantis Turns Heads with Comment that Citizens Insurance ‘Not Solvent;’. Link

- Ouazad, A. and Kahn, M. (2021) Mortgage Finance and Climate Change: Securitization Dynamics in the Aftermath of Natural Disasters. NBER Working Paper No. 26322. Link

- Smith, Adam B. (2023) “2022 U.S. Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters in Historical Context.” NOAA Climate.Gov. Link

- Bank of England (2022). Results of the 2021 Climate Biennial Exploratory Scenario. Link

- Kaya (2023) Transatlantic Divergence & Domestic Turbulence: EU & US ESG Policy Landscape Update; Kaya (2023) Climate-Related Financial Regulation & ESG Policy: 2023 EU, UK & US Outlook; Kaya (2023) US Climate Stress Testing – Federal Reserve Proposal, International Comparison & Implications.

- California Department of Insurance, Scenario Analysis: Assessing Climate Change Transition Risk in Insurer Portfolios (2018), Link.

- NYSDFS, An Analysis of New York Domestic Insurers’ Exposure to Transition Risks and Opportunities from Climate Change (June 10, 2021), Link.

- NAIC Climate Risk Disclosure Survey (2023). Link

- The Texas Tribune (2023). Lawmakers passed a bill to stop insurers from considering ESG criteria in setting rates. Link

- Executive Order on Climate-Related Financial Risk (2021). Link.

- Federal Insurance Office Request for Information on the Insurance Sector and Climate-Related Financial Risks (2021). Link

- Department of the Treasury (2021). FIO Proposed Climate Data Call Federal Register Notice. Link

- Federal Insurance Office (2023). Insurance Supervision and Regulation of Climate-Related Risks. Link

- Proposed Interpretive Guidance on Nonbank Financial Company Determinations (2023). Link

- Proposed Analytic Framework for Financial Stability Risk Identification, Assessment, and Response Factsheet Proposal (2023). Link

- DeMenno, M.B. (2022) Environmental sustainability and financial stability: can macroprudential stress testing measure and mitigate climate-related systemic financial risk? Journal of Banking Regulation. Link